SCARS Institute’s Encyclopedia of Scams™ Published Continuously for 25 Years

Authors:

• Tim McGuinness, Ph.D., DFin, MCPO, MAnth – Anthropologist, Scientist, Director of the Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

• Portions by the FBI

Article Abstract

The evolution of malware, malicious code, and computer viruses spans decades, from theoretical musings by mathematicians like John von Neumann in the 1940s to the sophisticated threats encountered in the digital landscape today.

Early experiments in self-replicating programs laid the groundwork for modern malware, with notable milestones including the Creeper worm in the 1970s and the emergence of macro viruses in the 1990s.

The advent of the internet unleashed a new era of cyber threats, exemplified by the Morris Worm of 1988 and the Melissa virus of 1999. As technology advanced, so did malware, with ransomware, botnets, and fileless malware becoming prevalent in the 21st century.

Looking ahead, the future of malware promises increased complexity and innovation, driven by trends such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and the blurring lines between cybercrime and espionage.

Effective defense against these evolving threats will require a multifaceted approach, including technological advancements, user education, and international cooperation.

A History of Malware, Malicious Code, and Computer Viruses: From Early Experiments to Modern Threats

In the Beginning, there was Just Code

The concept of malware, computer viruses, and malicious code infecting computer systems might seem like a recent invention, but its origins trace back further than you might think. This article explores the evolution of malware and computer viruses, from their theoretical beginnings to the sophisticated threats we face today.

Early Seeds of Destruction

The Theory Takes Root (1940s-1970s)

The idea of self-replicating programs, a core principle of malware and computer viruses, can be traced back to the 1940s. Hungarian mathematician John von Neumann theorized about such programs in his work on cellular automata. While never implemented, these concepts laid the groundwork for future developments.

Fast forward to the 1970s, and we see the first documented instance of a self-replicating program – the Creeper worm. Created by Robert Thomas in 1971, Creeper wasn’t designed to be malicious. It simply displayed a message on infected computers, highlighting potential security vulnerabilities on the early ARPANET network, a precursor to the internet.

The Floppy Disk Era

The Rise of Simple Threats (1970s-1980s)

The rise of personal computers in the 1970s and 80s coincided with the emergence of the first true malware threats. These early programs were relatively simple, and often spread via floppy disks, a popular method for sharing files at the time.

- Elk Cloner (1982): This early Apple II virus aimed to be more of a prank than a serious threat. It would display a poem on the infected computer.

- Brain (1986): Developed in Pakistan, the Brain is considered the first PC virus. Created by two brothers to deter software piracy, it infected the boot sector of floppy disks.

These early viruses primarily caused minor annoyances, but they highlighted the growing need for computer security measures.

The Dawn of the Internet

Worms Unleashed (1980s-1990s)

The arrival of the internet in the 1980s provided a new breeding ground for malware and computer viruses. Worms, self-replicating programs that exploit network vulnerabilities, became a major concern.

- Morris Worm (1988): Created by Robert Tappan Morris, this worm inadvertently caused widespread disruption on the early internet. Designed to gauge the size of the internet, a programming error made it replicate uncontrollably, overloading and slowing down numerous systems.

- Michelangelo (1991): This DOS virus targeted specific dates, attempting to overwrite data on infected machines. Thankfully, widespread media coverage and user preparedness helped mitigate its impact.

The Morris worm incident served as a wake-up call, demonstrating the potential for widespread damage through internet-borne malware.

Morris Worm – According to the FBI

At around 8:30 p.m. on November 2, 1988, a maliciously clever program (malware) was unleashed on the Internet from a computer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

This cyber worm (a kind of computer virus) was soon propagating at remarkable speed and grinding computers to a halt. “We are currently under attack,” wrote a concerned student at the University of California, Berkeley in an email later that night. Within 24 hours, an estimated 6,000 of the approximately 60,000 computers that were then connected to the Internet had been hit. Computer worms, unlike viruses, do not need a software host but can exist and propagate on their own.

Berkeley was far from the only victim. The rogue program had infected systems at a number of the prestigious colleges and public and private research centers that made up the early national electronic network. This was a year before the invention of the World Wide Web. Among the many casualties were Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, Johns Hopkins, NASA, and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

The worm only targeted computers running a specific version of the Unix operating system, but it spread widely because it featured multiple vectors of attack. For example, it exploited a backdoor in the Internet’s electronic mail system and a bug in the “finger” program that identified network users. It was also designed to stay hidden.

The worm did not damage or destroy files, but it still packed a punch. Vital military and university functions slowed to a crawl. Emails were delayed for days. The network community labored to figure out how the worm worked and how to remove it. Some institutions wiped their systems; others disconnected their computers from the network for as long as a week. The exact damages were difficult to quantify, but estimates started at $100,000 and soared into the millions.

As computer experts worked feverishly on a fix to this malware, the question of who was responsible became more urgent. Shortly after the attack, a dismayed programmer contacted two friends, admitting he’d launched the worm and despairing that it had spiraled dangerously out of control. He asked one friend to relay an anonymous message across the Internet on his behalf, with a brief apology and guidance for removing the program. Ironically, few received the message in time because the network had been so damaged by the worm.

Independently, the other friend made an anonymous call to The New York Times, which would soon splash news of the attack across its front pages. The friend told a reporter that he knew who built the program, saying it was meant as a harmless experiment and that its spread was the result of a programming error. In follow-up conversations with the reporter, the friend inadvertently referred to the worm’s author by his initials, RTM. Using that information, The Times soon confirmed and publicly reported that the culprit was a 23-year-old Cornell University graduate student named Robert Tappan Morris.

Morris was a talented computer scientist who had graduated from Harvard in June 1988. He had grown up immersed in computers thanks to his father, who was an early innovator at Bell Labs. At Harvard, Morris was known for his technological prowess, especially in Unix; he was also known as a prankster. After being accepted into Cornell that August, he began developing a program that could spread slowly and secretly across the Internet. To cover his tracks, he released it by hacking into an MIT computer from his Cornell terminal in Ithaca, New York.

After the incident became public, the FBI launched an investigation. Agents quickly confirmed that Morris was behind the attack and began interviewing him and his associates and decrypting his computer files, which yielded plenty of incriminating evidence.

But had Morris broken federal law? Turns out, he had. In 1986, Congress had passed the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, outlawing unauthorized access to protected computers. Prosecutors indicted Morris in 1989. The following year, a jury found him guilty, making him the first person convicted under the 1986 law. Morris, however, was spared jail time, instead receiving a fine, probation, and an order to complete 400 hours of community service.

The episode had a huge impact on a nation just coming to grips with how important—and vulnerable—computers had become to computer viruses. The idea of cybersecurity became something computer users began to take more seriously. Just days after the attack, for example, the country’s first computer emergency response team was created in Pittsburgh at the direction of the Department of Defense. Developers also began creating much-needed computer intrusion detection software.

At the same time, the Morris Worm inspired a new generation of hackers and a wave of Internet-driven assaults that continue to plague our digital systems to this day. Whether accidental or not, the first Internet attack was a wake-up call for the country and the cyber age to come.

Internet Malware Arrives

The Age of Email and Exploding Popularity (1990s-2000s)

The 1990s and 2000s saw a surge in malware designed to exploit the growing popularity of email and the rise of Microsoft Office.

- Macro Viruses: These viruses leveraged macros embedded in documents like spreadsheets to spread via email attachments. The Melissa worm (1999) is an infamous example.

- LoveLetter (2000): This VBScript worm exploited vulnerabilities in Microsoft Outlook to infect millions of machines.

- ILOVEYOU (2000): Masquerading as a love letter, this worm used social engineering tactics to trick users into opening an infected attachment.

These email-borne threats highlighted the need for user awareness and the importance of keeping software updated with security patches.

Melissa Virus – According to the FBI

A few decades ago, computer viruses—and public awareness of the tricks used to unleash them—were still relatively new notions to many Americans.

One attack would change that in a significant way.

In late March 1999, a programmer named David Lee Smith hijacked an America Online (AOL) account and used it to post a file on an Internet newsgroup named “alt.sex.” The posting promised dozens of free passwords to fee-based websites with adult content. When users took the bait, downloading the document and then opening it with Microsoft Word, a virus was unleashed on their computers.

On March 26, it began spreading like wildfire across the Internet.

The Melissa virus, reportedly named by Smith for a stripper in Florida, started by taking over victims’ Microsoft Word program. It then used a macro to hijack their Microsoft Outlook email system and send messages to the first 50 addresses in their mailing lists. Those messages, in turn, tempted recipients to open a virus-laden attachment by giving it such names as “sexxxy.jpg” or “naked wife” or by deceitfully asserting, “Here is the document you requested … don’t show anyone else ;-).” With the help of some devious social engineering, the virus operated like a sinister, automated chain letter.

The virus was not intended to steal money or information, but it wreaked plenty of havoc nonetheless. Email servers at more than 300 corporations and government agencies worldwide became overloaded, and some had to be shut down entirely, including at Microsoft. Approximately one million email accounts were disrupted, and Internet traffic in some locations slowed to a crawl.

Within a few days, cybersecurity experts had mostly contained the spread of the virus and restored the functionality of their networks, although it took some time to remove the infections entirely. Along with its investigative role, the FBI sent out warnings about the virus and its effects, helping to alert the public and reduce the destructive impacts of the attack. Still, the collective damage was enormous: an estimated $80 million for the cleanup and repair of affected computer systems.

Finding the culprit didn’t take long, thanks to a tip from a representative of AOL and nearly seamless cooperation between the FBI, New Jersey law enforcement, and other partners. Authorities traced the electronic fingerprints of the virus to Smith, who was arrested in northeastern New Jersey on April 1, 1999. Smith pleaded guilty in December 1999, and in May 2002, he was sentenced to 20 months in federal prison and fined $5,000. He also agreed to cooperate with federal and state authorities.

The Melissa virus, considered the fastest spreading infection at the time, was a rude awakening to the dark side of the web for many Americans. Awareness of the danger of opening unsolicited email attachments began to grow, along with the reality of online viruses and the damage they can do.

Like the Morris worm just over a decade earlier, the Melissa virus was a double-edged sword, leading to enhancements in online security while serving as inspiration for a wave of even more costly and potent cyberattacks to come.

For the FBI and its colleagues, the virus was a warning sign of a major germinating threat and of the need to quickly ramp up its cyber capabilities and partnerships.

Fittingly, a few months after Smith was sentenced, the Bureau put in place its new national Cyber Division focused exclusively on online crimes, with resources and programs devoted to protecting America’s electronic networks from harm. Today, with nearly everything in our society connected to the Internet, that cyber mission is more crucial than ever.

The Modern Era

A Landscape of Complexity (2000s-Present)

The 21st century has seen a dramatic increase in the sophistication and diversity of malware.

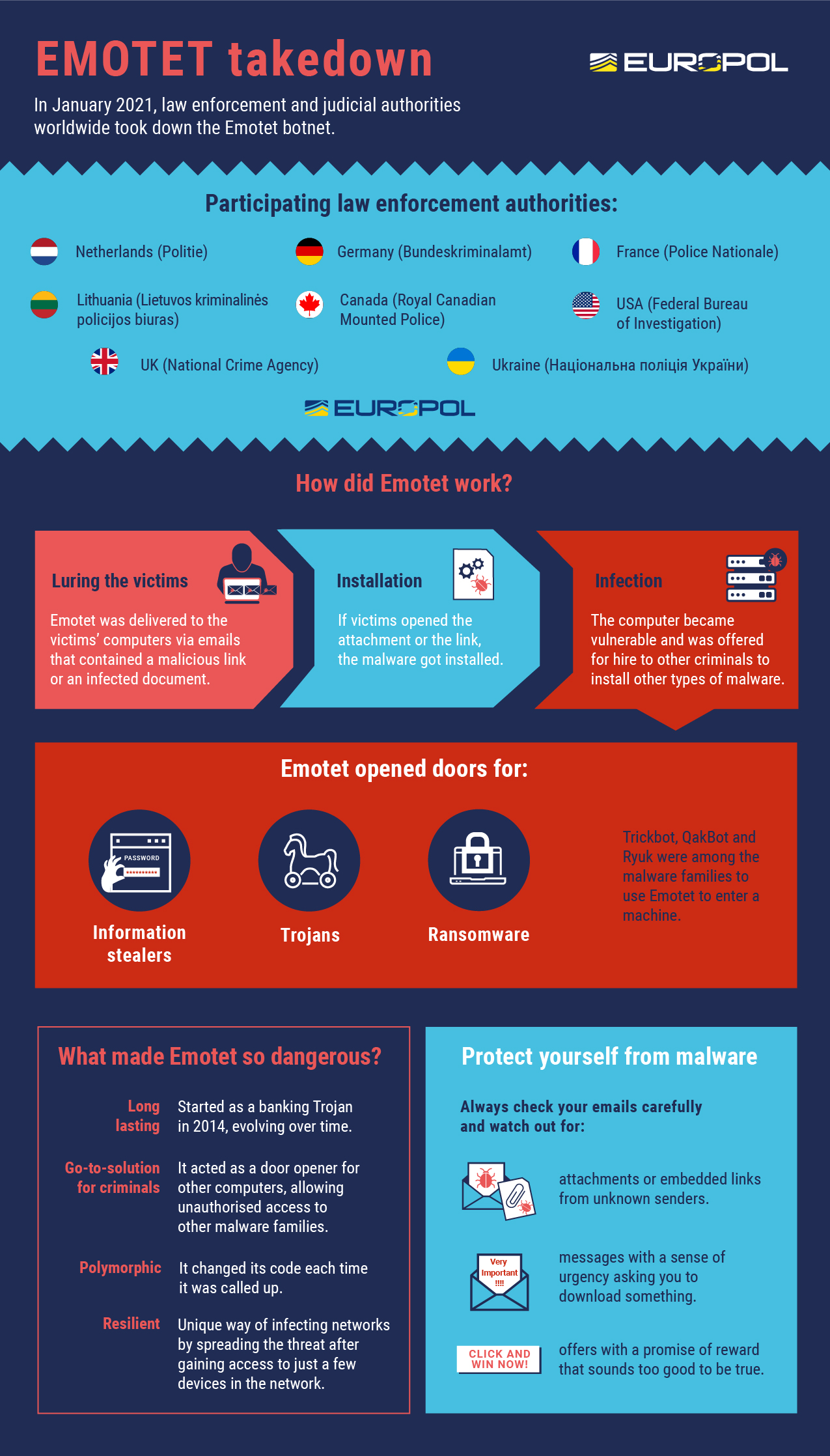

- Ransomware: This type of malware encrypts a victim’s data, demanding a ransom payment for decryption. CryptoLocker (2013) is an early example of this growing threat.

- Botnets: These networks of compromised computers, often controlled by attackers, can be used to launch large-scale denial-of-service attacks or distribute spam. The Mirai botnet attack of 2016 showcased the destructive potential of botnets.

- Spyware: Designed to steal personal information, spyware programs can be used for identity theft or financial fraud.

- Fileless Malware: This type of malware leverages legitimate system processes to avoid detection by traditional security software.

Cybercriminals have become increasingly professionalized, developing malware as a service (MaaS) models, and selling tools and expertise to less technical attackers.

The Future of Malware – A Continuous Arms Race

The battle against malware is a continuous arms race. As defenders develop new security measures, attackers constantly innovate new ways to bypass them. Here’s what we can expect in the coming years:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML)

Both sides are likely to leverage AI and ML. Attackers can use AI to develop more sophisticated malware that can evade detection and target specific vulnerabilities. Defenders can use AI to analyze vast amounts of data to identify and respond to threats faster.

The Internet of Things (IoT)

With billions of connected devices, the IoT presents a vast attack surface. Malicious actors can target these devices to launch distributed denial-of-service attacks or disrupt critical infrastructure.

The Rise of Ransomware 2.0

Ransomware attacks are likely to become even more sophisticated. Ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) will likely become even more prevalent, making it easier for less technical attackers to launch devastating attacks. Data exfiltration, where attackers steal sensitive data before encryption, might become more common, putting additional pressure on victims.

The Blurring Lines Between Crime and Espionage

: Nation-state actors are likely to continue using sophisticated malware for espionage purposes. These attacks might target critical infrastructure, steal intellectual property, or disrupt political processes.

Focus on Supply Chain Attacks

Hackers might target software development tools or cloud platforms to inject malware into widely used applications. This could have a ripple effect, infecting a large number of users at once.

Quantum Computing

While still in its early stages, the rise of quantum computing poses a significant challenge. Traditional encryption methods might become vulnerable to attacks from quantum computers. Developing new, quantum-resistant encryption methods will be crucial for protecting sensitive data in the future.

The Evolving Role of Security

Security will need to be a holistic approach, encompassing not just software and hardware, but also user education and awareness. Organizations will need to invest in security training for their employees to help them identify and avoid phishing attacks and other social engineering tactics.

International Cooperation

Cybersecurity threats are global. Effective defenses require international cooperation between governments, law enforcement agencies, and cybersecurity firms. Sharing information and coordinating efforts will be crucial for disrupting the activities of cybercriminal organizations.

What is the Difference?

Malware, computer viruses, malicious code, worms, trojans, and ransomware are all types of malicious software designed to infiltrate and damage computer systems, but they have distinct characteristics and functionalities:

- Malware: Malware is a broad term that encompasses any type of malicious software designed to disrupt, damage, or gain unauthorized access to computer systems or networks. It includes viruses, worms, trojans, ransomware, spyware, adware, and other malicious programs.

- Computer viruses: Computer viruses are a specific type of malware that infects a computer by attaching itself to legitimate programs or files and replicating when the infected program or file is executed. Viruses can cause a range of harmful effects, from corrupting data to compromising system integrity.

- Malicious code: Malicious code refers to any code or script designed to perform malicious actions on a computer system. It can include viruses, worms, trojans, and other types of malware.

- Worms: Worms are self-replicating malware that spreads across computer networks by exploiting vulnerabilities in operating systems or network protocols. Unlike viruses, worms do not require a host program to propagate and can spread independently.

- Trojans: Trojans, or Trojan horses, are malware disguised as legitimate software or files to trick users into downloading and executing them. Once installed, trojans can perform a variety of malicious activities, such as stealing sensitive information, installing additional malware, or granting unauthorized access to the infected system.

- Ransomware: Ransomware is a type of malware that encrypts files or locks users out of their systems and demands payment, usually in the form of cryptocurrency, to restore access. Ransomware attacks can have devastating consequences for individuals and organizations, often resulting in data loss or financial extortion.

While all these terms refer to malicious software, they differ in their methods of propagation, modes of operation, and specific malicious intents. Understanding these differences is crucial for effective cybersecurity and mitigating the risks associated with malware infections.

More Types

In addition to viruses, worms, trojans, and ransomware, there are several other types of malware commonly used by cybercriminals to compromise computer systems and networks. Some of these include:

- Spyware: Spyware is designed to secretly monitor and collect information about a user’s activities on their computer or device. It can capture keystrokes, record browsing habits, steal login credentials, and gather sensitive personal or financial information.

- Adware: Adware is software that displays unwanted advertisements, often in the form of pop-up ads, banners, or redirects, on a user’s computer. While not necessarily harmful, adware can be intrusive and disruptive to the user experience.

- Rootkits: Rootkits are stealthy malware that hides deep within a computer’s operating system to evade detection by antivirus software. Once installed, rootkits can give attackers full control over the infected system, allowing them to execute malicious commands, steal data, or launch further attacks.

- Keyloggers: Keyloggers, also known as keystroke loggers, are malware programs that record and log every keystroke typed on a computer or device. This allows attackers to capture sensitive information such as usernames, passwords, credit card numbers, and other confidential data.

- Botnets: Botnets are networks of compromised computers, or “bots,” that are controlled remotely by cybercriminals, often through command-and-control (C&C) servers. Botnets can be used to launch distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, send spam emails, steal data, or distribute malware to other computers.

- Backdoors: Backdoors are hidden entry points or vulnerabilities intentionally created by attackers to bypass security controls and gain unauthorized access to a computer or network. Once installed, backdoors can allow attackers to execute commands, upload or download files, or maintain persistent access to the compromised system.

- Exploits: Exploits are software vulnerabilities or weaknesses that attackers exploit to gain unauthorized access to a computer system or network. Exploits can target specific software applications, operating systems, or hardware components and are often used to deliver malware payloads or execute malicious commands.

- Fileless malware: Fileless malware operates entirely in memory, without leaving any traces on the infected system’s hard drive. This makes it more difficult to detect and remove by traditional antivirus software. Fileless malware often exploits legitimate system tools or processes to execute malicious commands and carry out attacks.

These are just a few examples of the many types of malware used by cybercriminals to compromise computer systems and networks. As cybersecurity threats continue to evolve, it’s essential for individuals and organizations to stay vigilant and implement effective security measures to protect against malware infections.

Summary

The future of malware is uncertain, but one thing is clear: the fight against it will be a constant battle. By staying informed about the latest threats and investing in robust security measures, individuals and organizations can help protect themselves from the ever-evolving dangers of malware.

More About Malware:

- Doxware – An Evolution In Malware/Extortionware (romancescamsnow.com)

- Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) (romancescamsnow.com)

- The Most Dangerous Malware EMOTET Disrupted Through Global Action (romancescamsnow.com)

- Negotiating Ransomware, Data Breach, & Cybercrime Payments 2024 (romancescamsnow.com)

- Ransomware Guide – A U.S. Government Report – DHS CISA December 2020 (romancescamsnow.com)

- SCARS™ CYBER BASICS: Ransomware (romancescamsnow.com)

- SCARS™ Cybersecurity Guide: Protecting Against Ransomware (romancescamsnow.com)

- Preserving The Evidence Of Scams And Safeguarding Justice For Scam Victims – 2024 (romancescamsnow.com)

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

Table of Contents

- Helping Everyone Understand the Cybersecurity Nightmare’s Beginnings

- Article Abstract

- A History of Malware, Malicious Code, and Computer Viruses: From Early Experiments to Modern Threats

- In the Beginning, there was Just Code

- Early Seeds of Destruction

- The Floppy Disk Era

- The Dawn of the Internet

- Morris Worm – According to the FBI

- Internet Malware Arrives

- Melissa Virus – According to the FBI

- The Modern Era

- The Future of Malware – A Continuous Arms Race

- What is the Difference?

- More Types

- Summary

- More About Malware:

LEAVE A COMMENT?

Recent Comments

On Other Articles

- Pat on What Is The Difference Between A Scam Victim And A Scam Survivor? [Updated]: “Due to my scams I don’t fully trust anyone online and I shouldn’t even those people I knew in high…” Mar 7, 12:46

- on SCARS 3 Steps For New Scam Victims 2024: “I was very fearful “he” would come to my home because I was knew my address, I spoke to someone…” Mar 7, 09:50

- on Sadness & Scam Recovery: “Before my scam, my mom passed away and I got a divorce, so I was dealing with the loss of…” Mar 7, 09:37

- on The Story Of Kira Lee Orsag (aka Dani Daniels) [Updated]: “There is NO evidence and she is not, she is a victim too. Sebastian, stop letting your anger think for…” Mar 6, 23:18

- on The Story Of Kira Lee Orsag (aka Dani Daniels) [Updated]: “There is real evidence that behind these two people there is something that not many people know. This woman is…” Mar 4, 03:58

- on Signs of Good & Bad Scam Victim Emotional Health: “ty this helps me with knowing why I cant quit eating when I am not hungry and when I crave…” Mar 2, 20:43

- on The SCARS Institute Top 50 Celebrity Impersonation Scams – 2025: “You should probably add Lawrence O’donnell as a scam also. I clicked on a site on tic tok for msnbc,…” Mar 2, 08:41

- on Finally Tax Relief for American Scam Victims is on the Horizon – 2026: “I just did my taxes for 2025 my tax account said so far for romances scam we cd not take…” Feb 25, 19:50

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “Yes, this is a scam. For your own sanity, just block them completely.” Feb 25, 15:37

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “She goes by the name of Sanrda John now” Feb 25, 10:26

ARTICLE META

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims

- Enroll in FREE SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery

If you are looking for local trauma counselors please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org or join SCARS for our counseling/therapy benefit: membership.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

A Note About Labeling!

We often use the term ‘scam victim’ in our articles, but this is a convenience to help those searching for information in search engines like Google. It is just a convenience and has no deeper meaning. If you have come through such an experience, YOU are a Survivor! It was not your fault. You are not alone! Axios!

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish, Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors experience. You can do Google searches but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

Statement About Victim Blaming

SCARS Institute articles examine different aspects of the scam victim experience, as well as those who may have been secondary victims. This work focuses on understanding victimization through the science of victimology, including common psychological and behavioral responses. The purpose is to help victims and survivors understand why these crimes occurred, reduce shame and self-blame, strengthen recovery programs and victim opportunities, and lower the risk of future victimization.

At times, these discussions may sound uncomfortable, overwhelming, or may be mistaken for blame. They are not. Scam victims are never blamed. Our goal is to explain the mechanisms of deception and the human responses that scammers exploit, and the processes that occur after the scam ends, so victims can better understand what happened to them and why it felt convincing at the time, and what the path looks like going forward.

Articles that address the psychology, neurology, physiology, and other characteristics of scams and the victim experience recognize that all people share cognitive and emotional traits that can be manipulated under the right conditions. These characteristics are not flaws. They are normal human functions that criminals deliberately exploit. Victims typically have little awareness of these mechanisms while a scam is unfolding and a very limited ability to control them. Awareness often comes only after the harm has occurred.

By explaining these processes, these articles help victims make sense of their experiences, understand common post-scam reactions, and identify ways to protect themselves moving forward. This knowledge supports recovery by replacing confusion and self-blame with clarity, context, and self-compassion.

Additional educational material on these topics is available at ScamPsychology.org – ScamsNOW.com and other SCARS Institute websites.

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this article is intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here to go to our ScamsNOW.com website.

Thank you for your comment. You may receive an email to follow up. We never share your data with marketers.