SCARS Institute’s Encyclopedia of Scams™ Published Continuously for 25 Years

The Impact On Scam Victims From Their Traumatic Memories

Memories of trauma are unique because of how brains and bodies respond to threat

Most of what you experience leaves no trace in your memory. Learning new information often requires a lot of effort and repetition — picture studying for a tough exam or mastering the tasks of a new job. It’s easy to forget what you’ve learned, and recalling details of the past can sometimes be challenging.

But some past experiences can keep haunting you for years. Life-threatening events — things like getting mugged or escaping from a fire — can be impossible to forget, even if you make every possible effort. Recent developments in the Supreme Court nomination hearings and the associated #WhyIDidntReport action on social media have rattled the public and raised questions about the nature, role and impact of these kinds of traumatic memories.

Threat responses are often accompanied by a range of sensations and feelings. Senses may sharpen, contributing to amplified detection and response to threat. You may experience tingling or numbness in your limbs, as well as shortness of breath, chest pain, feelings of weakness, fainting or dizziness. Your thoughts may be racing or, conversely, you may experience a lack of thoughts and feel detached from reality. Terror, panic, helplessness, lack of control or chaos may take over.

These reactions are automatic and cannot be stopped once they’re initiated, regardless of later feelings of guilt or shame about a lack of fight or flight.

Working With Traumatic Memories

This first section is from a Psychologists’ perspective speaking to other psychologists. When they say “clients’ they mean patients.

By Bessel van der Kolk, M.D. and Ruth Buczynski, Ph.D.; courtesy of NICABM

Sometimes we remember what seems like the smallest, most insignificant details of our lives – such as an 8th-grade locker combination, or a story heard at a party years ago, or all the lines from a favorite movie.

These memories – full of facts, words, and events – are explicit memories.

But there are different kinds of memories – ones that are evoked by sights, sounds, or even smells

For example, the smell of coffee percolating atop a gas stove could bring back Sunday afternoons around the table with beloved grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins.

On the other hand, being surprised by the scent of a particular aftershave, for instance, could elicit feelings of fear, panic, or even terror.

A person who was traumatized as a child might re-experience the all-too-familiar sensations of quivering in fear or breaking out in a cold sweat.

And it may have very little to do with the verbal thought process of, “Oh, this reminds me of the incident of my father hitting me.”

Traumatic memory is formed and stored very differently than everyday memory

So let’s take a closer look at what happens when a person experiences trauma.

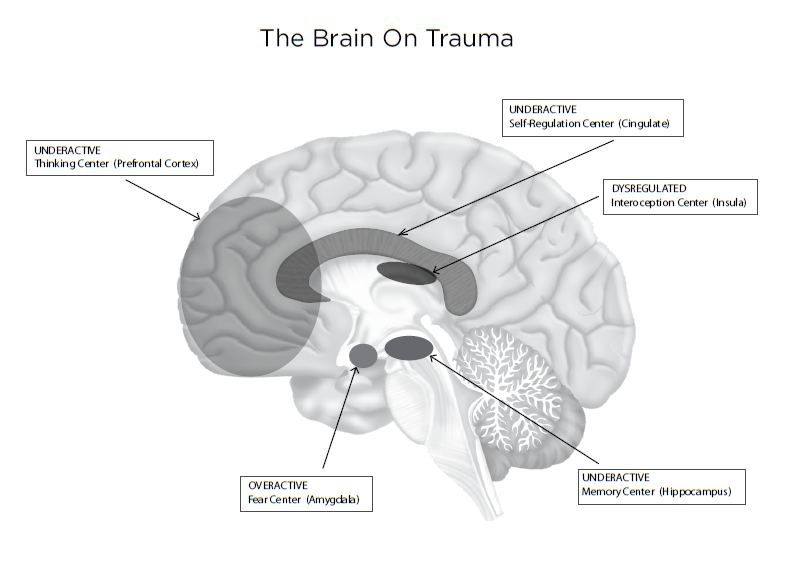

What Happens When the Brain Can’t Process Trauma

Dr. Van der Kolk: If a person was abused as a child, the brain can become wired to believe, “I’m a person to whom terrible things happen, and I better be on the alert for who’s going to hurt me now.”

Those are conscious thoughts that become stored in a very elementary part of the brain.

But what happens to adults when they become traumatized by something terrible they’ve experienced?

Simply put, the brain becomes overwhelmed. That’s because the thalamus shuts down and the entire picture of what happened can’t be stored in their brain.

“Instead of forming specific memories of the full event, people who have been traumatized remember images, sights, sounds, and physical sensations without much context.”

So instead of forming specific memories of the full event, people who have been traumatized remember images, sights, sounds, and physical sensations without much context.

And certain sensations just become triggers of the past.

You see, the brain continually forms maps of the world – maps of what is safe and what is dangerous.

“The brain continually forms maps of the world – maps of what is safe and what is dangerous.”

That’s how the brain becomes wired. People carry an internal map of who they are in relationship to the world. That becomes their memory system, but it’s not a known memory system like that of verbal memories.

It’s an implicit memory system

What that means is that a particular traumatic incident may not be remembered as a story of something that’s happened a long time ago. Instead, it gets triggered by sensations that people are experiencing in the present that can activate their emotional states.

It’s a much more elementary, organic level of a single sensation triggering the state of fear.

A person might keep thinking about the sensation and say, “Oh, this must be because it reminds me of the time that my father hit me.”

But that’s not the connection that the mind makes at that particular time.

How the Lack of Context Impacts Treatment

So what difference will it make in our work, knowing that a traumatic memory was encoded without context?

“It’s important to recognize that PTSD is not about the past. It’s about a body that continues to behave and organize itself as if the experience is happening right now.”

It’s important to recognize that PTSD or the experience of trauma is not about the past. It’s about a body that continues to behave and organize itself as if the experience is happening right now.

When we’re working with people who have been traumatized, it’s crucial to help them learn how to field the present as it is and to tolerate whatever goes on. The past is only relevant in as far as it stirs up current sensations, feelings, emotions, and thoughts.

The story about the past is just a story that people tell to explain how bad the trauma was, or why they have certain behaviors.

But the real issue is that trauma changes people. They feel different and experience certain sensations differently.

“ . . . the main focus of therapy needs to be helping people shift their internal experience.”

That’s why the main focus of therapy needs to be helping people shift their internal experience or, in other words, how the trauma is lodged inside them.

How Talking Can Distract a Client from Feeling

Now, in helping people learn to stay with their sensations, we need to resist the temptation to ask them to talk about their experience and what they’re aware of.

This is because talking can convey a defense against feeling.

Through the use of brain imagery, we’ve learned that when people are feeling something very deeply, one particular area of the brain lights up.

And we’ve seen other images taken when people are beginning to talk about their trauma and, when they do, another part of the brain lights up.

So talking can be a distraction from helping patients notice what is going on within themselves.

Non-verbal support is also important

“ . . . some of the best therapy is largely non-verbal.”

And that’s why the main task of the therapist is to help people to feel what they feel – to notice what they notice, to see how things flow within themselves, and to re-establish their sense of time inside.

Why Restoring the Sense of Time Can Make Emotions More Bearable

“All too often, when people feel traumatized, their bodies can feel like they’re under threat.”

Their bodies can feel like they’re under threat even if it’s a beautiful day and they’re in no particular danger.

So our task becomes helping people to feel those feelings of threat, and to just notice how the feelings go away as time goes on.

The body never stays the same because the body is always in a state of flux.

It’s important to help a patient learn that, when a sensation comes up, it’s okay to have it because something else will come next.

This is one way we can help patients re-establish this sense of time that gets destroyed by the trauma.

“Once a patient knows that something will come to an end, their whole attitude changes.”

Sensations and emotions become intolerable for clients because they think, “This will never come to an end.”

But once a patient knows that something will come to an end, their whole attitude changes.

Tips for Coping with Traumatic Memories

No two people are exactly alike. Your family background, health history, support system, and ways of relating to the world and processing emotions are some of the variables that make you an individual. This also means that two people who have experienced the very same traumatic event (such as a relationship scam) will emerge with very different memories and related emotions—and they may cope with their experience in similarly individual ways.

When you’re dealing with traumatic memories, then, it’s most important to find a coping strategy that works for you. It’s quite common that an effective coping strategy will consist of more than just one therapeutic intervention. Consider the following PTSD interventions, for example:

- Mindful breathing involves focusing on the rise and fall of one’s breath. When traumatic memories enter the realm of consciousness, the aim is to note these passing sensations matter-of-factly and non-judgmentally—but instead of giving them more attention, you refocus your attention on the rise and fall of your breath. Because traumatic memories will come and go, the idea is to learn how to ride out these sensations until they fade, by simply concentrating on one’s breath.

- “Mantram” meditation-based prayer (think “mantra”) improved symptoms of PTSD in veterans in a 2013 study. Like mindful breathing, this practice can be undertaken within the privacy of one’s home and consists of repeating a short, spiritual phrase in between breaths. The idea is to find a phrase that really speaks to you and what you most need when you’re facing a traumatic memory.

- Yoga has also been evidenced to help trauma survivors heal from difficult memories and emotions. Traumatic memories can lodge themselves in the body. The various positions, stretches, and breathing exercises of yoga can help release these sensations and build greater mind-body awareness toward greater resilience.

- EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) therapy is a form of psychotherapy that was specifically designed to alleviate the distress of traumatic memories. Research has proven EMDR effective at achieving this result. If you’re considering EMDR, I encourage you to find an EMDR-certified therapist.

- Support groups for trauma survivors can be therapeutic outlets in which to share what you are going through with those who understand, having experienced similar issues. Through Meetup, you should be able to find a group near you for trauma survivors and/or others with PTSD.

Learn More:

TAGS: SCARS, Information About Scams, Anti-Scam, Scams, Scammers, Fraudsters, Cybercrime, Crybercriminals, Romance Scams, Scam Victims, Online Fraud, Online Crime Is Real Crime, Scam Avoidance, Psychology of Scams, Trauma, PTSD, Traumatic Memories, Recovery, Victim Support

PLEASE SHARE OUR ARTICLES WITH YOUR FRIENDS & FAMILY

HELP OTHERS STAY SAFE ONLINE – YOUR KNOWLEDGE CAN MAKE THE DIFFERENCE!

THE NEXT VICTIM MIGHT BE YOUR OWN FAMILY MEMBER OR BEST FRIEND!

By the SCARS™ Editorial Team

Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

A Worldwide Crime Victims Assistance & Crime Prevention Nonprofit Organization Headquartered In Miami Florida USA & Monterrey NL Mexico, with Partners In More Than 60 Countries

To Learn More, Volunteer, or Donate Visit: www.AgainstScams.org

Contact Us: Contact@AgainstScams.org

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

Table of Contents

- Traumatic Memories Are Intensely Powerful And Come In Two Varieties

- Memories of trauma are unique because of how brains and bodies respond to threat

- What Happens When the Brain Can’t Process Trauma

- How the Lack of Context Impacts Treatment

- How Talking Can Distract a Client from Feeling

- Why Restoring the Sense of Time Can Make Emotions More Bearable

- PLEASE SHARE OUR ARTICLES WITH YOUR FRIENDS & FAMILY

- By the SCARS™ Editorial Team

Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc. - The Issue Of Race In Scam Reporting

Click Here To Learn More!

LEAVE A COMMENT?

Thank you for your comment. You may receive an email to follow up. We never share your data with marketers.

Recent Comments

On Other Articles

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “Yes, this is a scam. For your own sanity, just block them completely.” Feb 25, 15:37

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “She goes by the name of Sanrda John now” Feb 25, 10:26

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “So far I have not been scam out of any money because I was aware not to give the money…” Feb 25, 07:46

- on Love Bombing And How Romance Scam Victims Are Forced To Feel: “I was love bombed to the point that I would do just about anything for the scammer(s). I was told…” Feb 11, 14:24

- on Dani Daniels (Kira Lee Orsag): Another Scammer’s Favorite: “You provide a valuable service! I wish more people knew about it!” Feb 10, 15:05

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “We highly recommend that you simply turn away form the scam and scammers, and focus on the development of a…” Feb 4, 19:47

- on The Art Of Deception: The Fundamental Principals Of Successful Deceptions – 2024: “I experienced many of the deceptive tactics that romance scammers use. I was told various stories of hardship and why…” Feb 4, 15:27

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “Yes, I’m in that exact situation also. “Danielle” has seriously scammed me for 3 years now. “She” (he) doesn’t know…” Feb 4, 14:58

- on An Essay on Justice and Money Recovery – 2026: “you are so right I accidentally clicked on online justice I signed an agreement for 12k upfront but cd only…” Feb 3, 08:16

- on The SCARS Institute Top 50 Celebrity Impersonation Scams – 2025: “Quora has had visits from scammers pretending to be Keanu Reeves and Paul McCartney in 2025 and 2026.” Jan 27, 17:45

ARTICLE META

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims

- Enroll in FREE SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery

If you are looking for local trauma counselors please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org or join SCARS for our counseling/therapy benefit: membership.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

A Note About Labeling!

We often use the term ‘scam victim’ in our articles, but this is a convenience to help those searching for information in search engines like Google. It is just a convenience and has no deeper meaning. If you have come through such an experience, YOU are a Survivor! It was not your fault. You are not alone! Axios!

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish, Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors experience. You can do Google searches but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

Statement About Victim Blaming

SCARS Institute articles examine different aspects of the scam victim experience, as well as those who may have been secondary victims. This work focuses on understanding victimization through the science of victimology, including common psychological and behavioral responses. The purpose is to help victims and survivors understand why these crimes occurred, reduce shame and self-blame, strengthen recovery programs and victim opportunities, and lower the risk of future victimization.

At times, these discussions may sound uncomfortable, overwhelming, or may be mistaken for blame. They are not. Scam victims are never blamed. Our goal is to explain the mechanisms of deception and the human responses that scammers exploit, and the processes that occur after the scam ends, so victims can better understand what happened to them and why it felt convincing at the time, and what the path looks like going forward.

Articles that address the psychology, neurology, physiology, and other characteristics of scams and the victim experience recognize that all people share cognitive and emotional traits that can be manipulated under the right conditions. These characteristics are not flaws. They are normal human functions that criminals deliberately exploit. Victims typically have little awareness of these mechanisms while a scam is unfolding and a very limited ability to control them. Awareness often comes only after the harm has occurred.

By explaining these processes, these articles help victims make sense of their experiences, understand common post-scam reactions, and identify ways to protect themselves moving forward. This knowledge supports recovery by replacing confusion and self-blame with clarity, context, and self-compassion.

Additional educational material on these topics is available at ScamPsychology.org – ScamsNOW.com and other SCARS Institute websites.

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this article is intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here to go to our ScamsNOW.com website.

This is making more sense. Why certain sensations, the dark shadow of a tall man looming over me, the fear associated with the word trust, feeling helpless, fear swirling around me because of a color. Almost too fantastic to comprehend. So many times in the middle of the night I awake in terror without a clear idea of what is wrong.

Hopefully memory of the scam will help prevent it from happening again without causing further trauma.