SCARS Institute’s Encyclopedia of Scams™ Published Continuously for 25 Years

Authored By:

-

Principal Investigator: Professor Monica T. Whitty, Ph.D. (University of Leicester)

Originally Published: 2016 – Article Updated: 2023

Do You Love Me? Psychological Characteristics of Romance Scam Victims

Foreword By The Society of Citizens Against Romance Scams [SCARS]

For the purpose of enhancing scam victim understanding and victim assistance & support provider’s knowledge, we are presenting the study in its entirety without edits or comments.

While the results are the interpretation of the researcher and may differ from the practical experience of our organization over 33 years, we feel this is invaluable in expanding the understanding of the impacts on romance scam victims.

While some scam victims may feel like this reduces them to little more than lab rats, it is important to understand that such studies help us all better understand the impact that scams have on different individuals and help us develop better support and recovery solutions for victims.

Footnotes: throughout the text, you will find numbers at the end of phrases and sentences, these refer to the numbered references at the bottom of the document.

Do You Love Me? Psychological Characteristics of Romance Scam Victims

An Academic Study by Monica T. Whitty, Ph.D.Abstract

The online dating romance scam is an Advance Fee Fraud, typically conducted by international criminal groups via online dating sites and social networking sites. This type of mass-marketing fraud (MMF) is the most frequently reported type of MMF in most Western countries. This study examined the psychological characteristics of romance scam victims by comparing romance scam victims with those who had never been scammed by MMFs. Romance scam victims tend to be middle-aged, well-educated women. Moreover, they tend to be more impulsive (scoring high on urgency and sensation seeking), less kind, more trustworthy, and have an addictive disposition. It is argued here that these findings might be useful for those developing prevention programs and awareness campaigns.

Introduction

Mass-marketing fraud (MMF) is a type of fraud that exploits mass communication techniques (e.g., email, Instant Messenger, bulk mailing, social networking sites) to trick people out of money. One of the most well known of these is the 419 (Nigerian email scam), which existed in letter writing before the Internet. In the last 10 years we have witnessed an explosion of this crime on a global scale. In the United Kingdom in 2016, it was reported in the British Crime National survey that citizens are 10 times more likely to be robbed while at their computer by a criminal-based overseas than to fall victim of theft.1 Given the numbers of individuals scammed by MMF, there is an urgent need to understand in more detail the reasons why people are tricked and the kinds of people who are more vulnerable to becoming scammed.

The romance scam (also referred to as the online dating romance scam or the sweethearts scam) is of particular concern given the numbers of victims reported worldwide.1–6 The online dating romance scam is an Advance Fee Fraud, typically conducted by international criminal groups via online dating sites and social networking sites.6 Criminals pretend to initiate a relationship with the intention to defraud their victims of large sums of money. Scammers create fake profiles on dating sites and social networking sites with stolen photographs (e.g., attractive models, army officers) and a made-up identity. They develop an online relationship with the victim off the site, ‘‘grooming’’ the victim (developing a hyperpersonal relationship with the victim) until they feel that the victim is ready to part with their money.7,8 This scam has been found to cause a ‘‘double hit’’–a financial loss and the loss of a relationship. Whitty and Buchanan9 found that for some victims the loss of the relationship was more upsetting than their financial losses, with some victims describing their loss as the equivalent of experiencing a death of a loved one.

By studying MMF victimology we might be able to develop more effective methods to detect and prevent this type of crime. For example, we could learn more about who to target when conducting awareness campaigns or the most appropriate interventions according to personality type. This article reports empirical research examining the psychological characteristics of victims of romance scams. It is hoped that the findings will be applied in the crime prevention of romance scam and MMF in general.

Typology of Victims

There has been some speculation about the typology of fraud victims. Much of the work has focused on personal fraud, in general. For example, Titus and Gover10 believe that victims of fraud are more likely to be cooperative, greedy, gullible/uncritical, careless, susceptible to flattery, easily intimidated, risk takers, generous, hold respect for authority, and are good citizens. Fischer et al.11 found in their survey research that scam victims or near scam victims were more affected by the high values offered in scams and displayed a high degree of trust in the scammers. They also found some support for the notion that some kind of enduring personality trait might increase susceptibility to persuasion.

Similarly, a susceptibility to persuasion scale has been developed with the intention to predict likelihood of becoming scammed.12,13 This scale includes the following items: premeditation, consistency, sensation seeking, self-control, social influence, similarity, risk preferences, attitudes toward advertising, need for cognition, and uniqueness. The current work, therefore, suggests some merit in considering personal dispositions might predict likelihood of becoming scammed.

Romance Scam Typology

Some researchers have focused on specific types of MMFs. Lee and Soberon-Ferrer,14 for example, measured individuals’ vulnerability to consumer fraud and found that people with higher vulnerability scores tended to be older, poorer, less educated and single. Buchanan and Whitty15 found in their research on online dating romance scams that individuals with a higher tendency toward idealization of romantic partners were more likely to be scammed. Given the number of iterations of scams it may well be that some individuals are more susceptible to different types of fraud and so studying them separately might have some merit. This study builds upon the work on romance scam to investigate further the types of individuals who are more vulnerable to becoming financial victims of this crime.

Current Study

This study was interested in whether romance scam victims differ in personal characteristics compared with individuals who have not been scammed. Drawing from the previous literature on scamming compliance behavior and the research on behaviors related to certain personality dispositions, the below hypotheses were formulated for romance scam victims compared with nonvictims.

Age

There have been mixed findings on age differences and vulnerability to scams. Some suggest that older adults are more vulnerable to MMF,16,17 while others have found that older individuals are victimized to a similar extent to those in their midlife,18 those in their midlife are more likely to become victims compared to older and younger people.1,2 With regards to romance scams, it is often reported by authorities that victims are more likely to be middle aged.7,8 The first hypothesis therefore is that middle-aged people will be more likely than younger people or older people to be victims of romance scams (H1) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Gender

Although little is known about whether gender predicts likelihood of becoming scammed, in a study on the number of reports of being scammed in an Australian population it has been found that women are more likely to be scammed compared to men.1 It is therefore hypothesized that women are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H2) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Education

There is little known about whether more or less educated people are more likely to be scammed. Lee and SoberonFerrer14 found that less educated individuals were more likely to fall victim to consumer fraud. Being well educated might therefore be a protective factor against becoming defrauded by MMF. It is hypothesized that less educated people are more likely to be a victim of romance scam (H3) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scam.

Knowledge about cybersecurity

Research has found a clear distinction between experts and nonexperts regarding basic security behaviors, such as patching and updating software.19 Given that most romance scams involve the Internet, it is hypothesized that people who believe they know little about cybersecurity are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H4) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Impulsivity

Much of the literature that theorizes about why individuals become defrauded highlights the use of the scarcity tactic employed by criminals and their push for urgency to respond to a crisis.11 In romance scams, victims are often asked to urgently send money in an unexpected crisis.7,8 Modic and his colleagues have also suggested that individuals who are more likely to be sensation seeking, a form of impulsivity, are more likely to become scammed.12,13 It is hypothesized that individuals who score high on impulsivity are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H5) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Locus of control

Locus of control refers to an individual’s belief about control over his/her environment. People who have an internal locus of control have the conviction that events are contingent upon one’s behavior. Those with an external locus of control believe that events do not depend upon their actions, but rather upon luck, chance, or fate. If individuals believe that they have little control over events, they might be more likely to comply with a scammer. It is hypothesized that individuals who score high on external locus of control are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H6) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Trust in others (gullibility)

It is a popularly held belief in the media that scam victims are more likely to be gullible individuals.20 Titus and Gover’s10 review of the literature also found some evidence that victims of fraud are more trusting individuals. In Whitty’s 7,8 research on romance scam, victims described themselves as naı¨ve and trusting. It is hypothesized that individuals who score high on trust in others are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H7) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Trustworthy individual

Titus and Gover10 in their review of the literature of victims of scams found that victims tended to be ‘‘good citizens.’’ Fischer et al. found that scam victims and/or near scam victims displayed a high degree of trust. It is hypothesized that individuals who perceive themselves to be trustworthy people are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H8) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Kind

Little is known about whether the victims of MMF are more kind compared with nonvictims; however, given that many of the romance scam narratives involve a victim helping out another it is hypothesized that individuals who score high on a survey measuring kindness are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H9) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Greed

Some theorists have argued that victims of fraud tend to be greedy people.10 These theorists reason that the motivation for becoming involved in a scam is for self-gain, to make a large personal profit in a short amount of time. Given that many romance scam victims are often promised wealth as well as the perfect relationship it is hypothesized that individuals who score high on a survey measuring greed are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H10) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Addictive disposition

There has been some theorizing that individuals who get ‘‘caught up in a scam’’ do so because they are addicted to the scam itself and the visceral response they experience from the involvement in the scam. This was essentially identified in Whitty’s7,8 research on romance scam, when she argued that victims are similar to gamblers–both groups, she argued, are drawn into the addictive experience perceiving each stage as a ‘‘near win’’.7,8 It is therefore hypothesized that individuals who score high on an addictive disposition scale are more likely to be victims of romance scams (H11) compared with those who have not become victims of romance scams.

Methods

Participants

Overall, 12,060 participants who resided in the United Kingdom were recruited from a ‘‘Qualtrics’’ online panel. Of these individuals, 11,780 participants remained in the final sample. In this final sample 10,723 participants were not victims, 728 were one-off victims, and 329 were repeat victims. Of this sample, 200 participants had been scammed by the romance scam. Given that victims of scam may share some of the same dispositions as romance scam victims these participants were taken out of the final analysis.

Materials

Data were collected using a questionnaire hosted on the Qualtrics online survey platform. The questionnaire consisted of personality inventories and items devised to measure demographic descriptive data. Given that age group differences were hypothesized age was broken down into three categories: young 18–34 years, middle age 35–54 years, and older individuals 55 and over years. Impulsivity was measured using the UPPS-R Impulsivity Scale. The scale comprises four subscales: lack of premeditation, urgency, sensation seeking, and lack of perseverance. All of the subscales demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86, 0.91, 0.89, 0.83 for lack of premeditation, urgency, sensation seeking, and lack of perseverance, respectively). Locus of control was measured using the Internal-External Locus of Control scale. There was acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.65). Trust in others (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78), trustworthiness (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80), kindness (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81), and greed (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) were measured using items selected from the International Personality Item Pool. Addictive disposition was measured using the Eysenk Personality Questionnaire. Acceptable internal consistency was obtained for this scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.68). Knowledge of cybersecurity was measured using a single item, with participants rating their knowledge on a five-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicated the person believed they were very unknowledgeable about cybersecurity issues.

Procedure

Participants were recruited via a ‘‘Qualtrics’’ online panel. Participants were asked to complete a series of demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, education, knowledge about cybersecurity), personality items (e.g., impulsivity, locus of control, trust in others, trustworthiness, kindness, greed, addiction disposition), and whether they had been scammed

by MMF. They were also asked specially whether they had been scammed by the romance scam.Results

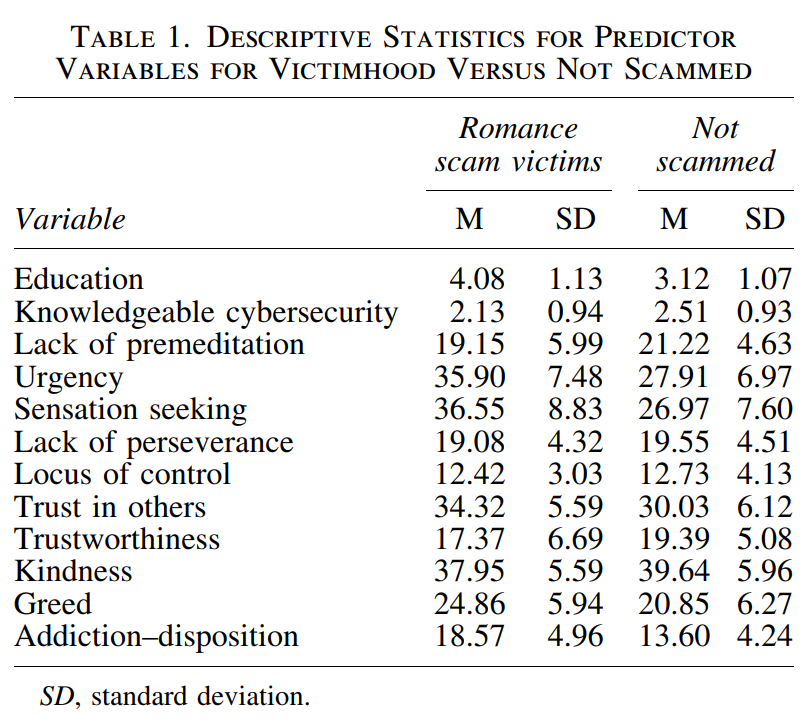

The analysis examined whether personal characteristics predicted whether someone became a romance scam victim by comparing those who had been scammed by romance scam with those who had never been scammed by any MMF. Descriptive statistics for each of the personal characteristics are outline in Table 1. In addition, 60 percent of women had been scammed by romance scam compared with 40 percent of men. With respect to age, 21 percent of the romance victims were younger people, 63 percent middle aged, and 16 percent older people. The hypotheses were tested simultaneously using standard forced entry binary logistic regression, with victimhood (scammed or not scammed) as the outcome variable. The overall model (Table 2) was significant in predicting victimhood [v2 (15, N= 10,923) = 666.16, p < 0.001], and the amount of variance explained was: Nagelkerke R2 = 0.354. Most of the hypotheses were supported. Two of the significant findings were in the opposite direction to what was predicted (H3 and H9) and there were no significant findings for H4, H6, H8, and H10.

Discussion

Although there is a paucity of research on the victimology of MMF victims, in line with previous research and thinking, this study supports the notion that specific psychological characteristics may predict the likelihood of becoming a victim of romance scams. The work adds to the previous literature and suggests there are other variables besides romantic beliefs15 that significantly predict likelihood of being tricked into giving money to a criminal pretending to be a genuine romantic partner. While the work here focuses solely on romance scam victims, the characteristics examined in this article might be considered when researching other types of scams–especially those which involve the development of an online relationship (friendship or romantic). An important message here is that romance scam victims tend to be middle-aged people–much more so than younger or older people. This is in contrast to the view that older people are more likely to become victims of scams.14 This finding suggests that some age groups might be more likely to become victims of certain types of scams and that policy developed to prevent victimization ought not focus entirely on the elderly. Perhaps the reason why middle-aged people are more vulnerable to romance scams is because this group of individuals have more disposable incomes and/or possibly this group are more likely to be seeking out partners on dating sites compared with other age groups.

Traits that measured impulsivity and lack of self-control, as hypothesised, predicted victimhood. Those tricked by romance scams are asked to comply quickly to the criminals’ requests,7 which perhaps explains why victims are more likely to score high on the impulsivity subscale of urgency. Moreover, victims are told elaborate and fantastical stories,7 which might explain why they score higher on sensation seeking compared with nonvictims. Victims are also more likely to score high on addiction characteristics compared with nonvictims, suggesting they find it difficult to pull away from the scam once introduced to the narrative. This is also in line with previous research that has found that victims find it difficult to believe they have been scammed even when told by law enforcement.7 Contrary to what was predicted, those who were more highly educated were also more vulnerable to becoming romance scam victims. This result contradicts popular belief that ‘‘stupid’’ people fall for scams. It may be that better educated people are more likely to use dating sites; however, this finding also suggests that being well educated does not necessarily protect individuals from becoming scammed. Fisher, Lea, and Evans11 have suggested that overconfidence can cause individuals to become more vulnerable to scams and it may well be that well-educated people are more confident that they can spot a romance scam. These speculations require future research and are important to consider when developing prevention programs. The finding that less kind individuals were more likely to be scammed by romance scams was less easy to explain. Perhaps, less kind individuals have fewer networks to help them check profiles or perhaps they seek out more harmful relationships. Kindness might also be a more transitory disposition. At the time of the scam, researchers have found that criminals isolate the victim from loved ones and push them to focus their time and resources on the fictitious relationship.7 They have also found that it is difficult for victims to rebuild their social networks after the scam has taken place. This might explain why victims of romance scams are less likely to rate highly items such as: ‘‘going out of their way to cheer up people who appear down,’’ ‘‘helping out a neighbor in the last month,’’ ‘‘getting excited by others good fortunes,’’ or ‘‘calling their friends when they are ill.’’ Overall, the findings reported here provide some new and important insights into the sorts of people who are scammed by romance scams. The findings have important implications for prevention and awareness raising programs. Dating sites and SNSs might draw from the information here to target certain types of people to make them aware of romance scams. Moreover, given that romance scam victims scored significantly higher on the addiction scale, programs that could be developed to prevent revictimization of romance scams might draw from programs that have been developed to prevent other addictive problems—such as alcoholics or

gamblers anonymous.Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council [EP/N028112/1].

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Address Correspondence to:

Prof. Monica Whitty

WMG, Cyber Security Centre

The University of Warwick

Coventry, CV4 7AL

United Kingdom

References

1. ONS Overview of fraud statistics: year ending March 2016.

2. ACCC Australians lose over $229 million to scams in 2015.

3. IC3 2015 Internet Crime Report. Federal Bureau of Investigation, International Crime Complaint Centre: USA. https://pdf .ic3.gov/2015_IC3Report.pdf (accessed Nov. 1, 2016).

4. NFA Annual Fraud Indicator. 2016

5. Whitty MT. Mass-marketing fraud: a growing concern. IEEE Security and Privacy 2015a; 13:84–87.

6. Whitty MT, Buchanan T. The Online dating romance scam: a serious crime. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2012; 15:181–183.

7. Whitty MT. The scammers persuasive techniques model: development of a stage model to explain the online dating romance scam. British Journal of Criminology 2013; 53: 665–684.

8. Whitty MT. Anatomy of the online dating romance scam. Security Journal 2015b; 28:443–455.

9. Whitty MT, Buchanan T. The online dating romance scam: the psychological impact on victims–both financial and non-financial. Criminology and Criminal Justice 2016; 16:176–194.

10. Titus RM, Gover AR. (2001) Personal fraud: the victims and the scams. In Farrell G, Pease K, eds. Repeat victimization: crime prevention studies. NY: Criminal Justice Press, Vol 12, pp. 133–151.

11. Fischer P, Lea SEG, Evans KM. Why do individuals respond to fraudulent scam communications and lose money? The psychological determinants of scam compliance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 2013; 43:2060–2072.

12. Modic D, Lea SEG. Scam compliance and the psychology of persuasion [preprint]. Social Sciences Research Network, 2013, Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2364464 (accessed Aug. 1, 2016).

13. Modic, D, Anderson RJ. We will make you like our research: the development of a susceptibility-to-persuasion scale (April 28, 2014). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2446971 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2446971 (accessed Aug. 1, 2016).

14. Lee J, Soberon-Ferrer H. Consumer vulnerability to fraud: influencing factors. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2005; 31: 70–89.

15. Buchanan T, Whitty MT. The online dating romance scam: causes and consequences of victimhood. Psychology, Crime and Law 2014; 20:261–283.

16. Alves LM, Wilson SR. The effects of loneliness on telemarketing fraud vulnerability among older adults. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect 2008; 20:63–85.

17. Oliver S, Burls T, Fenge L-A, et al. ‘‘Winning and losing’’: vulnerability to mass marketing fraud. The Journal of Adult Protection 2015; 17:360–350.

18. Smith R, Budd C. Consumer fraud in Australia: costs, rates and awareness of the risks in 2008. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice, 382, 2009.

19. Creese S, Hodges D, Jamison-Powell S, et al. (2013) Relationships between password choices, perceptions of risk and security expertise. In Marions L, Askoxylakis I, eds. Human aspects of information security, privacy and trust. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. Vol 8030, pp. 80–89.

20. Smith RG, Holmes MN, Kaufmann P. Nigerian Advance Fee Fraud. Australian Institute of Criminology: Trends & Issues in crime and criminal justice, 1999.

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

Table of Contents

- A Research Study About Romance Scam Victims

- Do You Love Me? Psychological Characteristics of Romance Scam Victims

- Foreword By The Society of Citizens Against Romance Scams [SCARS]

- Do You Love Me? Psychological Characteristics of Romance Scam Victims

An Academic Study by Monica T. Whitty, Ph.D. - Abstract

- Introduction

- Typology of Victims

- Romance Scam Typology

- Current Study

- Age

- Gender

- Education

- Knowledge about cybersecurity

- Impulsivity

- Locus of control

- Trust in others (gullibility)

- Trustworthy individual

- Kind

- Greed

- Addictive disposition

- Methods

- Participants

- Materials

- Procedure

- Results

- Discussion

- Acknowledgment

- Author Disclosure Statement

- Address Correspondence to:

- References

LEAVE A COMMENT?

Recent Comments

On Other Articles

- Arwyn Lautenschlager on Love Bombing And How Romance Scam Victims Are Forced To Feel: “I was love bombed to the point that I would do just about anything for the scammer(s). I was told…” Feb 11, 14:24

- on Dani Daniels (Kira Lee Orsag): Another Scammer’s Favorite: “You provide a valuable service! I wish more people knew about it!” Feb 10, 15:05

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “We highly recommend that you simply turn away form the scam and scammers, and focus on the development of a…” Feb 4, 19:47

- on The Art Of Deception: The Fundamental Principals Of Successful Deceptions – 2024: “I experienced many of the deceptive tactics that romance scammers use. I was told various stories of hardship and why…” Feb 4, 15:27

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “Yes, I’m in that exact situation also. “Danielle” has seriously scammed me for 3 years now. “She” (he) doesn’t know…” Feb 4, 14:58

- on An Essay on Justice and Money Recovery – 2026: “you are so right I accidentally clicked on online justice I signed an agreement for 12k upfront but cd only…” Feb 3, 08:16

- on The SCARS Institute Top 50 Celebrity Impersonation Scams – 2025: “Quora has had visits from scammers pretending to be Keanu Reeves and Paul McCartney in 2025 and 2026.” Jan 27, 17:45

- on Scam Victims Should Limit Their Exposure To Scam News & Scammer Photos: “I used to look at scammers photos all the time; however, I don’t feel the need to do it anymore.…” Jan 26, 23:19

- on After A Scam, No One Can Tell You How You Will React: “This article was very informative, my scams happened 5 years ago; however, l do remember several of those emotions and/or…” Jan 23, 17:17

- on Situational Awareness and How Trauma Makes Scam Victims Less Safe – 2024: “I need to be more observant and I am practicing situational awareness. I’m saving this article to remind me of…” Jan 21, 22:55

ARTICLE META

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims

- Enroll in FREE SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery

If you are looking for local trauma counselors please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org or join SCARS for our counseling/therapy benefit: membership.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

A Note About Labeling!

We often use the term ‘scam victim’ in our articles, but this is a convenience to help those searching for information in search engines like Google. It is just a convenience and has no deeper meaning. If you have come through such an experience, YOU are a Survivor! It was not your fault. You are not alone! Axios!

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish, Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors experience. You can do Google searches but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

Statement About Victim Blaming

SCARS Institute articles examine different aspects of the scam victim experience, as well as those who may have been secondary victims. This work focuses on understanding victimization through the science of victimology, including common psychological and behavioral responses. The purpose is to help victims and survivors understand why these crimes occurred, reduce shame and self-blame, strengthen recovery programs and victim opportunities, and lower the risk of future victimization.

At times, these discussions may sound uncomfortable, overwhelming, or may be mistaken for blame. They are not. Scam victims are never blamed. Our goal is to explain the mechanisms of deception and the human responses that scammers exploit, and the processes that occur after the scam ends, so victims can better understand what happened to them and why it felt convincing at the time, and what the path looks like going forward.

Articles that address the psychology, neurology, physiology, and other characteristics of scams and the victim experience recognize that all people share cognitive and emotional traits that can be manipulated under the right conditions. These characteristics are not flaws. They are normal human functions that criminals deliberately exploit. Victims typically have little awareness of these mechanisms while a scam is unfolding and a very limited ability to control them. Awareness often comes only after the harm has occurred.

By explaining these processes, these articles help victims make sense of their experiences, understand common post-scam reactions, and identify ways to protect themselves moving forward. This knowledge supports recovery by replacing confusion and self-blame with clarity, context, and self-compassion.

Additional educational material on these topics is available at ScamPsychology.org – ScamsNOW.com and other SCARS Institute websites.

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this article is intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here to go to our ScamsNOW.com website.

Thank you for your comment. You may receive an email to follow up. We never share your data with marketers.