SCARS Institute’s Encyclopedia of Scams™ Published Continuously for 25 Years

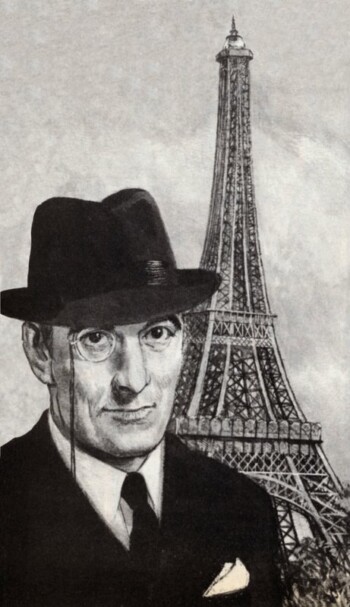

Victor Lustig – The Classic Con Man

Victor Lustig: the Con Artist Who Sold the Eiffel Tower and Outfoxed Al Capone

Bio of a Fraudster – A SCARS Institute Insight

Authors:

• SCARS Institute Encyclopedia of Scams Editorial Team – Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

• Vianey Gonzalez B.Sc(Psych) – Psychologist, Certified Deception Professional, Psychology Advisory Panel & Director of the Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

• Tim McGuinness, Ph.D., DFin, MCPO, MAnth – Anthropologist, Scientist, Director of the Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

Originally Published: 2012 – Article Updated: 2023

See Author Biographies Below

Article Abstract

Victor Lustig’s career traces the rise and fall of a con artist who turned charm, preparation, and psychology into a global enterprise. Born in Bohemia in 1890, he honed languages and manners on Atlantic liners before debuting the Romanian Box, a staged “money duplicator” that sold on spectacle and delay. In 1925, he forged titles and letters to stage a secret auction that convinced a Paris scrap dealer that the Eiffel Tower would be dismantled for salvage. In Chicago, he coaxed a gratuity from Al Capone by appearing unusually honest. The early 1930s brought industrial counterfeiting with engraver William Watts, whose high-quality notes finally drew sustained Secret Service pursuit. Arrest, a brief escape, and recapture ended with a long sentence at Alcatraz. He died in federal custody in 1947. His method relied on restricted rooms, polished props, and listening that mapped each target’s pride and fears, turning trust into his most reliable tool.

Victor Lustig: the Con Artist Who Sold the Eiffel Tower and Outfoxed Al Capone

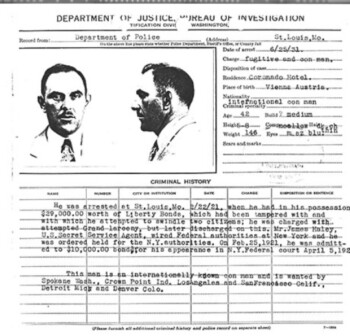

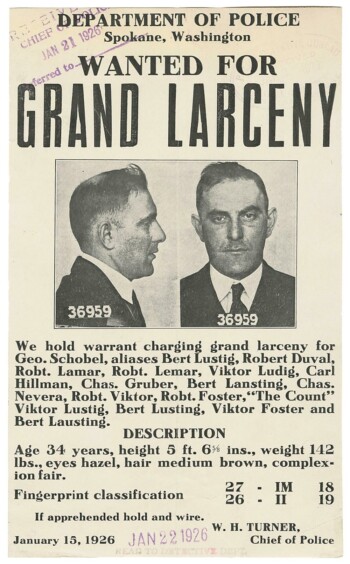

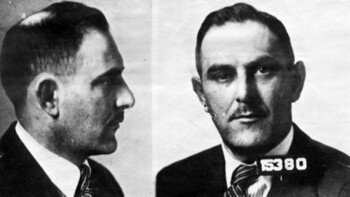

Victor Lustig’s career reads like a catalogue of twentieth-century fraud. Born in 1890 in the Bohemian town of Hostinné, then within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he came of age in a Europe that prized wit, language, and social polish. He learned French and German early, developed an ear for accents, and discovered that good manners opened doors that credentials could not. Before his thirtieth birthday, he had passed through boarding schools and card rooms, made acquaintances among travelers on transatlantic liners, and learned to study people the way a locksmith studies tumblers. Out of those experiences came a criminal method that prized preparation, patience, and performance. He called himself “Count” when it helped, dressed the part when needed, and treated every swindle like theater, with scripts, props, and rehearsals. The stage he chose was the modern city. The cities he favored were Paris, Vienna, New York, and Chicago.

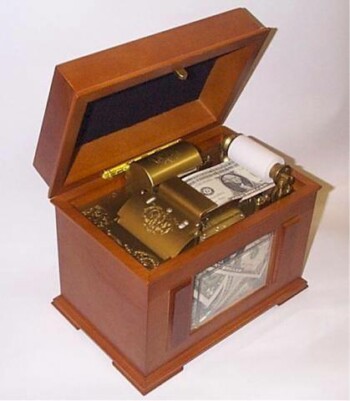

Early Swindles and the “Romanian Box”

Lustig’s first great hit was a portable illusion. In the 1910s and early 1920s, he traveled with a polished wooden contraption fitted with rollers and slots. He introduced it as a miraculous device that could “duplicate” currency by chemically transferring ink from genuine notes to blank paper. He would feed a real bill into the machine with a solvent packet hidden within, pause for the proper effect, and then produce, on schedule, a second bill bearing the right serials and seals. His audience, primed by suggestion and dazzled by timing, watched an authentic note slide out and concluded that the box worked. He sold boxes for thousands of dollars, each accompanied by a demonstration and a polite warning that the “duplication” took hours, which bought him time to vanish before confusion turned to anger. The story became part of con-man lore, and versions of it surfaced across the United States and Europe throughout the 1920s.

The Steamship Classrooms of the Atlantic

Ocean liners served as his universities and hunting grounds. First-class decks collected merchants, officials, and showmen who believed themselves world-wise. Lustig learned to read the small tells: a watch checked too often, a wallet flashed a little too proudly, a ring tapped on a mahogany rail. He offered card games, investment tips, and sympathetic conversation in equal measure. He delivered credibility through restraint, frequently letting an early “opportunity” pass to build the impression of caution. By the time a mark decided to ask for an introduction or a piece of advice, Lustig had already drawn the boundaries of trust. He preferred soft hooks over hard sells, and he left enough silence for greed and vanity to do their work.

Selling the Eiffel Tower

In the spring of 1925, Paris was busy with postwar repairs and civic projects. The Eiffel Tower, a colossal iron structure raised for the 1889 exposition, had become expensive to maintain. Newspapers carried debates about its future, discussing budgets and the burden of upkeep. Lustig recognized an opening in the public mood. Working with an accomplice, he drafted government-looking stationery, forged a ministry title for himself, and summoned a small group of scrap dealers to a discreet meeting at the Hôtel de Crillon. The pitch was radical and confidential: the French government, he claimed, had decided to dismantle the Eiffel Tower and sell it for scrap. The plan required secrecy to avoid public outrage, and the dealers were invited to bid for the contract. The room, the letterhead, and the whispered urgency made the fiction breathe.

Among the invited bidders, a businessman named André Poisson proved the most promising. Lustig studied him, gauging both ambition and insecurity. He cultivated Poisson’s trust outside the meeting, hinting at worries about “political complications” and allowing the man to infer that a discrete gratuity might help. When Poisson paid the bribe and transferred funds for the “contract,” Lustig knew the con had reached its crest. He and his partner left France immediately. Poisson, stung twice over by the loss and the shame, chose not to report the crime, which helped protect the swindler’s legend. The audacity of the theft turned Paris into a rumor mill, and the rumor matured into a famous claim: the man who sold the Eiffel Tower.

Accounts from the period insist he tried again. Within months, he allegedly sent a second round of letters to scrap dealers, inviting bids a second time. This effort faltered when a skeptical merchant contacted the authorities. Lustig, sensing attention, fled the country before the police reached his hotel. Whether or not the “second sale” reached the cash stage, the attempt shows his appetite for scale and his confidence in secrecy as a shield. In any case, Paris had grown too hot. He turned his attention to America, where his English and charm offered fresh cover.

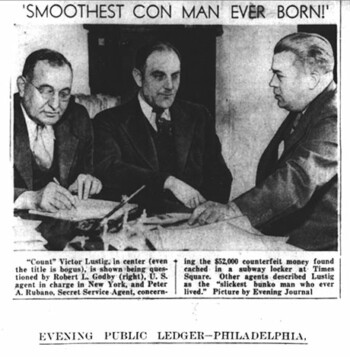

A Con on Al Capone

Chicago in the late 1920s carried its own legends. One of them wore tailored suits and ran an empire. Lustig approached Al Capone not as a supplicant but as a businessman. He borrowed a substantial sum, reportedly five thousand dollars, and promised to double it in sixty days through an unspecified venture. He then deposited the money untouched in a bank. Two months later, he returned to Capone, apologized, and explained that the investment had failed. He returned the full amount without excuses. The gesture shocked the gangster, who rewarded the “honesty” with a thousand-dollar gratuity for the effort. That gratuity, not the principal, had been the target all along. The psychology was simple: when a man expects to be cheated, straightforward behavior disarms him. The story, told and retold, cemented Lustig’s reputation for nerve and showmanship.

Counterfeiting with William Watts

The Great Depression brought new opportunities and new risks. In the early 1930s, Lustig partnered with William Watts, a skilled engraver, to mount a large-scale counterfeiting operation. Watts supplied plates and paper that fooled shopkeepers and even bankers at a glance, while Lustig built the distribution network. The team floated high-quality bills into circulation city by city to avoid concentrated suspicion. For a time, the flow of bogus notes looked like a rising tide. The U.S. Secret Service, responsible for safeguarding currency, took notice as complaints about strange serials and unusual paper increased. Investigators eventually traced patterns that pointed toward a Midwestern hub and then toward familiar names.

Arrest, Escape, and Recapture

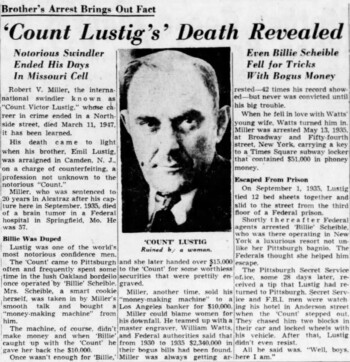

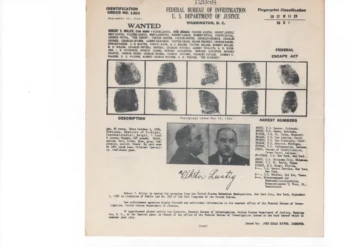

In 1935, U.S. federal agents closed in. Lustig was arrested and charged with counterfeiting, conspiracy, and related offenses. He briefly escaped custody, reportedly by fashioning a rope from bedsheets and scaling a window, but his freedom proved short. He was caught again in Pittsburgh and delivered to federal court. On conviction, he received a twenty-year sentence and an additional five years to run concurrently for an earlier violation. The Bureau of Prisons designated him for the new federal penitentiary on Alcatraz Island, which housed inmates the government considered escape risks or management problems. There he joined a roster that included bootleggers and bank robbers whose names filled headlines.

Alcatraz and the End of the Performance

Life on Alcatraz stripped performances to routine. The island’s regimented days left little room for improvisation. Yet even behind the walls Lustig remained a figure of curiosity, a prisoner whose past exploits had crossed oceans and borders. His health declined during the 1940s. Tuberculosis and pneumonia weakened him, and in 1947 he died at the federal medical center in Springfield, Missouri. The man who had adopted dozens of aliases ended with a name written in prison files and a cause of death recorded by a government he had spent years outsmarting. The con artist’s final act, in that sense, surrendered to the same rules he had long tried to bend.

Craft, Method, and the Code He Lived By

Observers have often described Lustig’s “ten commandments” for con men, a set of maxims that emphasize patience, listening, and the avoidance of alcohol on the job. Whether those rules were his own coinage or a distillation of the subculture’s best practices, they match the record of how he worked. He studied victims quietly, let others talk, and rarely rushed pressure points. He understood the environment and props. He dressed a little better than necessary and chose grand rooms for private meetings. He wrote letters on expensive paper and stamped them with forged seals. He preferred to have marks come to him rather than chase them. He arranged scenes where the victim’s choice felt voluntary. He then exited cleanly, leaving as few threads as possible.

The Eiffel Tower affair shows those principles in full. He used current events to build plausibility. He limited access to boost the sense of privilege. He courted not the richest scrap dealer but the most suggestible, one whose ambition outpaced his caution. He seeded the idea of a “facilitation” payment without stating it plainly, making the bribe feel like an initiative taken by the victim rather than a demand from the impostor. He left France before the victim could consult rivals or lawyers. In each phase, he treated time as a tool.

The Capone con reveals another part of his method: he understood expectations. The gangster expected a grift and braced for it. By violating that expectation with apparent honesty, Lustig created a vacuum of trust that pulled money toward him. He exploited not only greed but the hunger for relief from suspicion. That insight, more than the counterfeit plates or the wooden box, set him apart.

Public Appetite for Audacity

Lustig flourished because cities rewarded audacity. The 1920s and early 1930s ran on spectacle. World’s fairs, skyscrapers, transatlantic crossings, and jazz clubs filled newspapers with images of possibility. In such a climate, a man with a smooth accent and official stationery could slip through doors never meant for him. He learned that spectacle discourages questions. He also learned that shame silences victims. The scrap dealer who bought the Eiffel Tower kept his embarrassment private, which allowed the legend to grow unchecked. The silence of the mark, repeated case after case, became part of the con itself.

Law enforcement learned in turn. The Secret Service, born in the nineteenth century to fight counterfeiting, matched Lustig’s patience with its own. Agents compared bills, followed small distributors, interviewed printers, and waited for human error. The arrest record that survives, with dates and docket numbers and a clipped description of the man in custody, speaks a language far colder than the hotel lobbies where the crimes began. It is the language that ended his career.

The Afterlife of a Reputation

Stories about Lustig’s feats have circulated for decades, shaped by memoirs, newspaper features, and later histories. Some details vary by teller, as often happens with figures who worked in shadows. What remains consistent is the portrait of a man who treated fraud as performance and who chose victims as much for their needs as for their means. That portrait explains why his name remains shorthand for elaborate confidence tricks. It also explains why his career, though painted in bright colors, serves as a cautionary study in the workings of trust.

A con depends less on the con artist than on the human traits he recruits. Desire for advantage, impatience with procedure, fear of missing out, and reluctance to seek a second opinion all become levers in the right hands. Lustig’s hands proved very skilled. He avoided crowded rooms when privacy helped, selected settings where people felt special, and kept the props of authority close. He delivered compliments sparingly and curiosity generously. He placed people where they could talk themselves into doing what he wanted.

A Timeline of Major Operations

By 1919 he had built a reputation aboard steamships as a smooth cardsharp and opportunist who preferred conversation to threats. Through the early 1920s, he sold his currency-“duplicating” box to businessmen who believed they had acquired a revolutionary device. In 1925 he carried out the Eiffel Tower swindle in Paris, using forged identities and a careful auction script to take payment and bribes from a single buyer before fleeing. Within the year, he attempted a follow-up approach but left the country when scrutiny grew. By the late 1920s he had crossed to the United States with enough polish to approach Chicago’s most famous crime boss and enough calm to run a delayed-gratification trick that won him a tidy profit at minimal risk. In the early 1930s he turned to counterfeiting at scale with William Watts, sending high-quality notes across state lines until the Secret Service closed in. Arrest, escape, recapture, trial, and a twenty-year sentence followed in 1935. He spent the last years of his life in federal custody and died in 1947.

Reading the Man Behind the Mask

Descriptions from agents and contemporaries stress composure. He spoke softly. He listened longer than most. He moved gracefully among languages and learned the etiquette of each city he visited. He drank little while working. He valued neatness in dress and paperwork alike. These traits helped him in rooms where credentials mattered and in places where appearances mattered even more. The contrast between that elegance and the harm his schemes produced is stark. Businesses lost cash, reputations suffered, and counterfeit currency rippled outward to people far removed from the meetings where the plots began. He belonged to an era that loved its rascals, but the law he broke and the people he injured had to live with the consequences after the punch lines faded.

What His Story Explains

The Eiffel Tower scandal is unforgettable because it pairs a literal national monument with the private vices of pride and secrecy. The Capone trick endures because it applies the same insight to a figure who embodied menace. Together, they show how fraudsters select settings that amplify emotions. A symbol inspires awe, and awe makes detail seem beneath notice. Power inspires fear, and fear makes gratitude feel like safety. Lustig arranged both settings and let psychology carry the rest.

The counterfeiting phase illustrates something else, a shift from bespoke swindles to industrial ones. It required a capable partner, better equipment, and a distribution map that looked like a business plan. It also drew law enforcement into a more systematic response, with forensic attention to paper, ink, and serials. The battle between artful thieves and organized investigators moved from hotel suites to laboratories and ledgers. That battle shaped the modern Secret Service as surely as it shaped the end of Lustig’s freedom.

A Closing Portrait

Victor Lustig fit the era that made him famous. He wore tailored suits at a time when cloth announced rank. He wrote on heavy stationery when paper felt like power. He addressed men by title and learned the names of their wives. He organized meetings in rooms whose mirrors doubled the glow of chandeliers. He treated the world like a stage and props as if they were evidence. Underneath the staging sat a set of quiet skills: concentration, patience, and the nerve to leave before applause.

His story still circulates because it is entertaining and instructive at once. It entertains by its scale and its audacity, by the image of a foreign gentleman selling a tower and tipping his hat as he boards a train. It instructs by revealing how quickly confidence, once extended, can be turned against the person who grants it. The line between invitation and intrusion often runs through a single handshake. Lustig shook many hands. He taught law enforcement to follow the money and ordinary people to be wary of secrets that flatter. He died in custody with his health spent, but his legend kept traveling, retold in magazines, memoirs, and true-crime columns that marvel at the ease with which a practiced liar could make the improbable feel routine. That ease was his art and his ruin.

Today, the Eiffel Tower still rises over Paris, a monument to engineering and to the city that built it. The name Victor Lustig lingers nearby in the cultural memory, a reminder that even solid iron can serve as a stage for a story about human credulity. His life traces the arc of a con that grew from card tables to headlines, from jokes told in bars to indictments read in court. It ends where such arcs tend to end, with a record number in a file and a bed in a prison hospital. Between those poles ran a career that chronicled the tactics of trust and the price of misusing it. That is why the tale continues to travel, long after the actor left the stage.

Glossary

- Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary — This term refers to the high-security U.S. prison where Victor Lustig served his sentence. It symbolizes the end point of many sophisticated fraud careers and shows how persistence by investigators can overcome years of deception.

- Alias — This term describes a false name adopted to create a new identity. It allows a con artist to separate crimes from a true biography and to move across borders and social circles with less scrutiny.

- André Poisson — This term identifies the Paris scrap dealer targeted in the Eiffel Tower swindle. His role illustrates how ambition and embarrassment can keep a victim silent after a loss.

- Audacity — This term captures the bold scale of a scheme, such as proposing to sell a landmark. It often shocks targets into accepting details they might otherwise question.

- Bribe Facilitation — This term describes a planted suggestion that a discreet payment will smooth “political complications.” It converts a bribe into what feels like the victim’s own idea, which deepens guilt and silence later.

- Bureau of Prisons — This term names the U.S. agency that manages federal inmates and assigned Lustig to Alcatraz. It represents the institutional response that eventually contains prolific offenders.

- Capone Con — This term covers Lustig’s short play on Al Capone, where money was “borrowed,” held safely, then returned to earn a reward. It shows how unexpected honesty can be used to trigger trust and profit.

- Confidence Game — This term defines any scheme that profits by winning trust first and extracting money second. It depends on believable roles, controlled settings, and the target’s desire to feel chosen.

- Counterfeiting — This term refers to producing fake currency designed to pass as genuine. It harms entire communities by spreading losses beyond the first exchange.

- Counterfeit Distribution Network — This term describes the planned movement of bogus notes through several cities to avoid detection. It uses volume, timing, and distance to delay pattern recognition by banks and police.

- Disciplined Listening — This term identifies the habit of letting a target talk freely while the con artist notes needs and fears. It turns conversation into a map for later pressure points.

- Discreet Meeting — This term describes a small, invitation-only gathering staged to create a sense of privilege. It narrows dissenting voices and increases the chance that flattery will override caution.

- Eiffel Tower Swindle — This term names the 1925 Paris con in which a forged official proposed scrapping the tower. It demonstrates how public debates and maintenance costs can be twisted into a believable pretext.

- Engraving Plates — This term refers to the specialized metal plates used to print counterfeit bills. Their quality determines how long fake money can circulate before detection.

- Escape by Bedsheets — This term recalls Lustig’s brief jailbreak using improvised rope. It highlights how risk-taking often continues after arrest and why secure custody matters.

- Forged Letterhead — This term describes counterfeit stationery that imitates government or corporate branding. It gives documents visual authority that persuades targets to lower their guard.

- Forensic Currency Analysis — This term covers laboratory and field tests on paper, ink, and serial numbers. It provides the evidence path that links scattered losses to a single source.

- Government-Looking Stationery — This term refers to professional paper stock and seals that imitate official communications. It works because people often trust familiar symbols more than they test content.

- Grand Hotel Setting — This term identifies the use of prestigious venues to signal legitimacy. Elegant surroundings can mute skepticism and make secrecy feel proper.

- Hôtel de Crillon — This term names the Paris hotel used as a stage for the tower “auction.” It shows how location alone can confer status on a false proposal.

- Impostor Official — This term describes a fraudster who assumes a government title to command obedience. The role pressures targets to comply quickly and avoid public questions.

- Industrial-Scale Fraud — This term refers to schemes that move from one-off tricks to systematic operations, such as large counterfeiting runs. Scale increases damage and attracts federal attention.

- Ink Transfer Illusion — This term explains the “Romanian Box” demonstration in which a real bill appears to duplicate. The timed reveal convinces observers that a physics-breaking device exists.

- Jazz Age Spectacle — This term describes the 1920s environment of fairs, skyscrapers, and showmanship. A culture of display makes large lies feel consistent with the times.

- Key Props — This term refers to physical items like seals, boxes, and contracts used to sell a story. Props anchor fiction in the senses and help victims overlook missing facts.

- Law Enforcement Patience — This term highlights the slow, methodical work of linking complaints over time. It counters a con artist’s speed with careful accumulation of proof.

- Legend Building — This term describes how repeated stories about past exploits create a protective aura. A reputation for success can make the next victim more eager to participate.

- Mark — This term identifies the chosen target of a con. Selection focuses on suggestibility and need rather than wealth alone.

- Ministry Title Forgery — This term refers to inventing a government role to oversee a fake project. It leverages bureaucracy’s complexity to discourage verification.

- Nonreporting by Victims — This term describes a victim’s choice to stay silent due to shame or fear. Silence protects the offender and allows schemes to repeat.

- Ocean Liner Classroom — This term captures the way first-class decks served as training grounds for reading people. Travel environments create temporary communities where status cues are easy to exploit.

- Postwar Paris — This term describes the civic climate of repairs and budget debates that framed the 1925 con. Real public issues gave the false proposal a plausible backdrop.

- Props and Staging — This term refers to the planned arrangement of room, timing, and paperwork to direct emotions. Good staging reduces the need for complicated lies.

- Quiet Exit — This term describes leaving a city or country immediately after payment. It prevents cross-checks and limits the window for complaints.

- Romanian Box — This term names the portable device Lustig sold as a money-duplicator. It relied on sleight, chemicals, and delay to transform awe into payment.

- Rumor Mill Protection — This term explains how an unreported loss becomes a private rumor rather than a police case. Rumor spreads the legend while hiding the evidence.

- Scrap Dealer Auction — This term describes the fake, sealed-bid process used to sell the Eiffel Tower “contract.” Competitive tension encourages rash decisions and bribe offers.

- Secrecy as Shield — This term refers to framing a scheme as confidential to limit outside advice. It isolates the target and keeps reality checks at bay.

- Secret Service Pursuit — This term names the U.S. agency that investigates counterfeit currency. Its jurisdiction and expertise make it the long-term counterweight to organized fraud.

- Shame-Induced Silence — This term describes the self-blame that keeps victims from seeking help. It can be reduced by normalizing reporting and focusing on the crime, not the person.

- Showmanship — This term identifies the performative layer of speech, dress, and timing that sells a lie. It turns an ordinary claim into a persuasive event.

- Ten Commandments of the Con — This term summarizes maxims about patience, sobriety, and careful observation attributed to Lustig. Such rules formalize habits that increase a scheme’s chances of success.

- Timing and Delay — This term refers to the deliberate use of waiting periods, such as “duplication time,” to buy an escape window. Delay converts curiosity into belief and belief into payment.

- Trust Vacuum — This term describes the relief a target feels when expected cheating does not occur, as in the Capone story. That relief opens the door to voluntary reward.

- Uniform of Respectability — This term names the visual cues of tailored dress and good manners that signal credibility. Polished appearance lowers defenses before any facts are checked.

- Vienna–Paris–New York Circuit — This term describes the transatlantic path that supported fresh identities and new targets. Mobility kept authorities and rumors from catching up.

- William Watts — This term identifies the engraver who partnered with Lustig on high-quality counterfeit notes. The partnership shows how technical skill and social engineering can combine to widen harm.

- World’s Fair Legacy — This term refers to the exposition era that produced icons like the Eiffel Tower. Tying a lie to a famous symbol increases emotional impact and reduces scrutiny.

Author Biographies

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

Table of Contents

- Victor Lustig: the Con Artist Who Sold the Eiffel Tower and Outfoxed Al Capone

- Victor Lustig: the Con Artist Who Sold the Eiffel Tower and Outfoxed Al Capone

- Early Swindles and the “Romanian Box”

- The Steamship Classrooms of the Atlantic

- Selling the Eiffel Tower

- A Con on Al Capone

- Counterfeiting with William Watts

- Arrest, Escape, and Recapture

- Alcatraz and the End of the Performance

- Craft, Method, and the Code He Lived By

- Public Appetite for Audacity

- The Afterlife of a Reputation

- A Timeline of Major Operations

- Reading the Man Behind the Mask

- What His Story Explains

- A Closing Portrait

- Photo Gallery

- Glossary

LEAVE A COMMENT?

Recent Comments

On Other Articles

- SCARS Institute Editorial Team on The Story Of Kira Lee Orsag (aka Dani Daniels) [Updated]: “There is NO evidence and she is not, she is a victim too. Sebastian, stop letting your anger think for…” Mar 6, 23:18

- on The Story Of Kira Lee Orsag (aka Dani Daniels) [Updated]: “There is real evidence that behind these two people there is something that not many people know. This woman is…” Mar 4, 03:58

- on Signs of Good & Bad Scam Victim Emotional Health: “ty this helps me with knowing why I cant quit eating when I am not hungry and when I crave…” Mar 2, 20:43

- on The SCARS Institute Top 50 Celebrity Impersonation Scams – 2025: “You should probably add Lawrence O’donnell as a scam also. I clicked on a site on tic tok for msnbc,…” Mar 2, 08:41

- on Finally Tax Relief for American Scam Victims is on the Horizon – 2026: “I just did my taxes for 2025 my tax account said so far for romances scam we cd not take…” Feb 25, 19:50

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “Yes, this is a scam. For your own sanity, just block them completely.” Feb 25, 15:37

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “She goes by the name of Sanrda John now” Feb 25, 10:26

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “So far I have not been scam out of any money because I was aware not to give the money…” Feb 25, 07:46

- on Love Bombing And How Romance Scam Victims Are Forced To Feel: “I was love bombed to the point that I would do just about anything for the scammer(s). I was told…” Feb 11, 14:24

- on Dani Daniels (Kira Lee Orsag): Another Scammer’s Favorite: “You provide a valuable service! I wish more people knew about it!” Feb 10, 15:05

ARTICLE META

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims

- Enroll in FREE SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery

If you are looking for local trauma counselors please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org or join SCARS for our counseling/therapy benefit: membership.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

A Note About Labeling!

We often use the term ‘scam victim’ in our articles, but this is a convenience to help those searching for information in search engines like Google. It is just a convenience and has no deeper meaning. If you have come through such an experience, YOU are a Survivor! It was not your fault. You are not alone! Axios!

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish, Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors experience. You can do Google searches but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

Statement About Victim Blaming

SCARS Institute articles examine different aspects of the scam victim experience, as well as those who may have been secondary victims. This work focuses on understanding victimization through the science of victimology, including common psychological and behavioral responses. The purpose is to help victims and survivors understand why these crimes occurred, reduce shame and self-blame, strengthen recovery programs and victim opportunities, and lower the risk of future victimization.

At times, these discussions may sound uncomfortable, overwhelming, or may be mistaken for blame. They are not. Scam victims are never blamed. Our goal is to explain the mechanisms of deception and the human responses that scammers exploit, and the processes that occur after the scam ends, so victims can better understand what happened to them and why it felt convincing at the time, and what the path looks like going forward.

Articles that address the psychology, neurology, physiology, and other characteristics of scams and the victim experience recognize that all people share cognitive and emotional traits that can be manipulated under the right conditions. These characteristics are not flaws. They are normal human functions that criminals deliberately exploit. Victims typically have little awareness of these mechanisms while a scam is unfolding and a very limited ability to control them. Awareness often comes only after the harm has occurred.

By explaining these processes, these articles help victims make sense of their experiences, understand common post-scam reactions, and identify ways to protect themselves moving forward. This knowledge supports recovery by replacing confusion and self-blame with clarity, context, and self-compassion.

Additional educational material on these topics is available at ScamPsychology.org – ScamsNOW.com and other SCARS Institute websites.

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this article is intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here to go to our ScamsNOW.com website.

Thank you for your comment. You may receive an email to follow up. We never share your data with marketers.