SCARS Institute’s Encyclopedia of Scams™ Published Continuously for 25 Years

The Scam States of Southeast Asia

How the “Scam States” of Southeast Asia Developed and are Now Dominating the Region

Geopolitics of Scams – A SCARS Institute Article

Author:

• Tim McGuinness, Ph.D., DFin, MCPO, MAnth – Anthropologist, Scientist, Director of the Society of Citizens Against Relationship Scams Inc.

See Author Biographies Below

Article Abstract

Scam states in Southeast Asia have emerged as a dominant global hub for cyber-enabled fraud, forced criminality, and human trafficking. Criminal syndicates, often linked to transnational networks, operate walled compounds where trafficked workers are forced to run romance scams, cryptocurrency fraud, and other schemes that generate tens of billions in illicit revenue each year. These operations thrive in regions with weak governance, corruption, and conflict, gaining political and economic influence as illicit profits fuel local development and employment. Thousands of trafficked individuals endure violence, coercion, and torture while targeting victims worldwide who frequently lose life-changing sums of money. Despite international crackdowns, sanctions, and rescue operations, scam infrastructure continues to adapt and expand, posing sustained risks to global financial security and human rights.

How the “Scam States” of Southeast Asia Developed and are Now Dominating the Region

From Small Frauds to Industrial-Scale Cybercrime

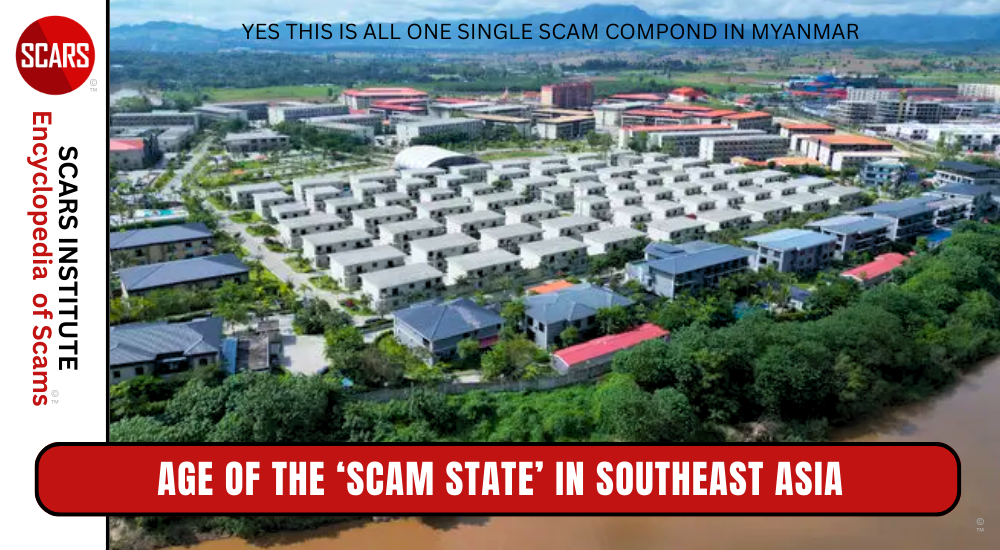

Over the past decade, Southeast Asia has transformed into the world’s largest hub for industrial-scale online fraud, human trafficking, and cyber-enabled financial crime. What began as loose rings of internet scammers sending spam or phishing emails has evolved into vast operations deeply embedded in regional economies. Entire networks of criminal syndicates, often originating from Chinese organized crime groups, now run large “scam centers”, compounds where trafficked or coerced workers operate nonstop to defraud victims worldwide.

These scam centers function as factories of deception: staff are locked in dormitories or guarded compounds; passports are confiscated; victims are forced to work long hours under threat, torture, or debt bondage. The scale is staggering: recent reports estimate that hundreds of thousands of people in Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos are involved, many involuntarily, with annual global scam revenues reaching tens of billions of dollars.

By 2025, analysts have begun to refer to parts of Southeast Asia as “scam states,” akin to narco-states, where the fraudulent economy becomes a dominant engine for local wealth, corruption, and political influence.

Root Causes

War, Weak Governance, and Economic Opportunity

Several structural factors enabled this transformation. In Myanmar, the 2021 military coup and ensuing civil war dismantled governance and the rule of law in many border regions. Criminal syndicates exploited this instability, seizing abandoned casinos and hotels or converting failing gambling resorts into cyber-fraud centers. Previously, these groups made money through casinos and gambling tourism; when pandemic lockdowns shut down travel, the shift to online scams became a lifeline.

In neighboring countries such as Cambodia and Laos, weak institutional oversight, porous borders, and limited enforcement created fertile ground for these operations. Transnational criminal networks consolidated these advantages to build complex, mobile systems, “fraud factories” that can be relocated at short notice when authorities show interest.

Trafficking networks recruit vulnerable individuals through fake job offers spread over social media, promising high-paying work abroad. Once these victims cross the border, they are subjected to control, violence, and forced labor inside scam compounds.

Modus Operandi

Romance, Crypto, AI, and Global Reach

The scams themselves have become highly sophisticated. The dominant model now is the so-called “pig-butchering” scheme, a combination of romance scam and investment fraud. Scammers cultivate a convincing online relationship, build trust, then urge victims to invest large sums in bogus cryptocurrency platforms.

To make the deception even more effective, operators rely on modern tools: AI-powered chatbots to maintain constant contact, deepfake video calls to impersonate attractive or trustworthy personas, and cloned phishing websites that mimic legitimate exchanges or banking portals.

Victims worldwide, often from Europe, North America, and East Asia, lose hundreds of thousands of dollars each in many cases. One survey cited losses averaging $155,000 per victim, with most losing more than half of their net worth.

The global reach of these operations has drawn attention from governments and law enforcement. In late 2025, the United States announced a new Scam Center Strike Force to target these Southeast Asia–based cybercriminal networks. The U.S. Department of Justice characterized the phenomenon as a national security threat, linking stolen funds to cryptocurrency investment scams and money laundering.

Economic and Political Entrenchment

When Fraud Becomes a Pillar of Local Economies

These scams have become so profitable that in some regions they rival or surpass legitimate industries. According to recent estimates, scam-related activity in certain Mekong subregion countries now contributes tens of billions annually, in some cases matching or exceeding significant sectors of the formal economy.

This infusion of illicit capital has produced economic dependencies: criminal networks have become de facto employers for local populations, often providing electricity, jobs, and other benefits, which complicates efforts to dismantle them.

In some instances, links between scam operations and local political elites appear to enable impunity. These operations thrive on a combination of corruption, weak oversight, and, in some cases, protection or complicity from armed or state-affiliated groups. A high-profile example was the international sanctions imposed in 2025 on a crime network run by the “Prince Group,” accused of using trafficked workers in Cambodia and laundering profits through real estate, gambling, and cryptocurrency mining.

Although recent crackdowns, raids, arrests, power shutdowns, and internet blackouts have dismantled some compounds, operators often relocate just ahead of enforcement actions, shifting operations to new remote locations. Experts warn that such crackdowns serve largely as political theatre rather than effective suppression.

Human Cost

Forced Labor, Abuse, and Human Rights Violations

Beyond money lost by foreign victims, the human suffering inside these scam centers is enormous. Many workers are themselves victims of human trafficking, lured under false job adverts and then trapped in abusive, prison-like compounds. Reports from human rights organisations describe routine torture, solitary confinement, electric shocks, brutal beatings, sexual abuse, and death, including among children trafficked into these centers.

International NGOs and observers have criticized certain governments for ignoring or enabling these abuses. In Cambodia, for example, authorities have been accused of neglecting the problem, failing to investigate hundreds of known scam sites, and failing to identify or aid victims, even when child labor and modern-slavery conditions are confirmed.

Crackdowns have led to some rescue operations and arrests. In mid-2025, Cambodia announced over 2,100 arrests and the deportation of more than 2,300 foreign nationals associated with scam operations. Still, many compounds remain active. Amnesty International identified 53 confirmed scam centers, but highlighted that many more suspected sites had neither been investigated nor shut down.

From Casinos to Cyber Fraud Factories

Over the past decade, parts of Southeast Asia have shifted from being transit points for traditional crime to becoming command centers of a global online fraud industry. In border towns and special economic zones in Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, and neighboring states, criminal networks have turned former casino districts and new-purpose compounds into what survivors describe as “fraud factories.” These sites house thousands of people forced to run romance scams, investment traps, fake cryptocurrency platforms, and impersonation schemes targeting victims around the world.

The transformation accelerated when China cracked down on phone fraud and illegal gambling operations within its borders. Syndicates relocated across borders into lightly governed zones in the Mekong region. There, they leased or built walled compounds, registered shell companies, and bought protection from local power brokers. The result is a new criminal geography sometimes described by analysts as “scam states,” where parts of a country’s territory and institutions are effectively repurposed to shelter and profit from industrial-scale cyber scams.

A Multi-Billion-Dollar Shadow Industry

The economic weight of this industry is staggering. A United Nations analysis of scam centers in Cambodia estimated that fraud operations there alone generate between 12.5 and 19 billion dollars annually, a figure that could equal as much as 60 percent of Cambodia’s official gross domestic product. Those estimates include proceeds from online investment fraud, romance scams, illegal gambling, and other cyber-enabled crimes concentrated in cities such as Sihanoukville, Phnom Penh, and Bavet.

Region-wide, international organizations now treat cyber scam compounds as one of the most lucrative forms of organized crime in East and Southeast Asia, rivaling narcotics and illegal logging.

UN reports and independent researchers describe vertically integrated business models. Criminal groups recruit workers, move them across borders, confiscate their passports, and assign them to “desks” that operate scripted frauds around the clock. Profits are laundered through cryptocurrency, underground banking systems, and complicit financial institutions, making it difficult for law enforcement to trace or recover funds.

For local elites and security forces willing to tolerate or participate in these operations, scam estates bring in foreign capital, construction projects, and steady cash flows, even as they damage the country’s reputation and expose citizens to exploitation. The economic temptation helps explain why crackdowns have been uneven and why compounds frequently reappear under new names after highly publicized raids.

Trafficking Humans into “Fraud Factories”

Behind the screen of glossy office towers and neon-lit casinos lies a system that international agencies now classify as human trafficking for forced criminality. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the International Organization for Migration report that tens of thousands of people from across Asia and beyond have been deceived with fake job offers and delivered into scam compounds in Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos, and neighboring states.

A 2024 United Nations estimate suggested that 100,000 to 150,000 people may have been trafficked into scam centers in Cambodia alone (some estimates make it ten times that), many of them foreign nationals lured by online advertisements promising high salaries in “IT,” customer service, or cryptocurrency trading. Similar patterns have been documented in Myanmar’s border areas, particularly in hubs such as Myawaddy and the wider Golden Triangle, where mega compounds like “KK Park” became infamous for cybercrime and forced labor before recent military operations claimed to have retaken some of the sites.

Victims come from China, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, South Asia, and increasingly from Africa and Latin America. Many report that upon arrival, their passports are seized and they are sold or transferred between companies. Escape attempts can lead to beatings, electric shocks, or being resold to even harsher operators.

Inside the Compounds

Work, Punishment, and Escape

Inside scam centers, daily life is structured around maximizing fraudulent output. Survivors describe large open-plan offices filled with rows of computers and phones where workers are assigned to specialized roles. Some build trust on dating apps and messaging platforms. Others shift targets into “investment” chats. A different team handles fake trading dashboards, forged documents, and scripted “customer support.” Performance is tracked in real time, with quotas for the number of new “clients” contacted, conversations converted, and amounts extracted.

Those who fail to meet targets report verbal abuse, fines, forced overtime, or physical punishment. Accounts gathered by human rights organizations describe detainees being deprived of sleep, beaten with sticks, shocked with electric batons, or locked in small punishment rooms. Some are threatened with being sold to operations that focus on more violent crimes. Others are told that their families will be harmed or that they will be framed for serious offenses if they refuse to work.

Attempts to escape are risky. Compounds are often surrounded by high walls, barbed wire, and armed guards. Local police can be complicit or unwilling to intervene. Many workers rely on families to pay “redemption fees” to buy their release, mirroring older debt bondage patterns. Only when embassies, NGOs, or international agencies become involved do some detainees manage to leave, and even then, they may face arrest or stigma when they return home because their labor involved criminal activity.

State Complicity

Weak Governance and Corruption

The rise of scam states is tightly connected to governance gaps and corruption. In several countries, scam operations flourished in special economic zones, border areas, or regions controlled by armed groups where central authorities had limited oversight. There, criminal investors could form partnerships with local businessmen, politicians, or militia leaders, paying for protection and access to land and infrastructure.

International human rights bodies have criticized some governments for failing to protect trafficked workers and for treating rescued scam laborers as immigration offenders instead of victims. Reports from United Nations agencies note patterns in which police raids free a portion of detainees while suspected organizers disappear or quickly resume business under new corporate fronts.

At the same time, there is growing pressure from powerful neighboring states whose citizens are heavily targeted. China has mounted extensive law enforcement campaigns with regional partners, pressing governments to shut down compounds and extradite suspects.

Since 2023, Chinese and Myanmar authorities have reportedly detained more than 57,000 people in joint operations targeting cybercrime and scam networks, a figure that reflects both the scale of the industry and the breadth of the dragnet.

China and Regional Governments Push Back

Facing public outrage over rising fraud losses, several Southeast Asian governments have launched high-profile operations against scam estates. In Cambodia, authorities have conducted raids in Sihanoukville and other hotspots, rescuing trafficked workers and seizing equipment, while pledging to tighten regulation of foreign-owned businesses and special economic zones.

In Myanmar, the situation is more complex because different armed actors control territory hosting scam centers. Reports describe competing claims of crackdowns by the military junta and by ethnic armed organizations, each asserting that they have dismantled compounds such as KK Park and freed thousands of workers. Independent verification is difficult in conflict zones, and human rights groups warn that some operations appear to reshuffle rather than eliminate criminal infrastructure.

Regional police cooperation has intensified. INTERPOL has coordinated multi-country actions to identify victims of trafficking into scam compounds and to target the financial flows that sustain these centers. The organization has warned that the model has “globalized,” with cyber scam hubs now affecting victims in every region and involving tens of thousands of people held against their will for online fraud.

The International Response

Sanctions, Strike Forces, and the Challenge Ahead

Growing recognition of the scale and severity of the problem has spurred an international response. In late 2025, the United States and the United Kingdom jointly sanctioned a major criminal network operating across Southeast Asia, the “Prince Group”, for cryptocurrency investment scams, fraud, money laundering, and trafficking. The sanctions targeted 146 people connected to the operation and froze assets, including properties in London.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s newly formed Scam Center Strike Force aims to disrupt these fraud networks by tracing funds, shutting down money-laundering channels, and coordinating with foreign governments.

At the same time, civil society and human-rights organizations are campaigning for victim protection, rescue operations, and government accountability. Some governments in the region, previously hesitant or complicit, are now under rising domestic and international pressure to act.

However, experts caution that the structural roots of the “scam state” phenomenon, corruption, weak governance, economic inequality, porous borders, and high demand for foreign investment and cheap labor, are deep. Unless reforms address these systemic issues, crackdown efforts may only displace the problem rather than eliminate it.

Looking Forward

Why the Scam Industry Is Hard to Eradicate

The resilience of scam operations lies in their adaptability, mobility, and profitability. Operators design their networks to be intangible: they rely on digital communication, online platforms for scams, and cryptocurrency for laundering, all difficult to trace. When one location is raided, another emerges elsewhere in the region. This mobility turns enforcement into a game of whack-a-mole.

Unlike traditional crimes such as drug trafficking, scams don’t require physical contraband. They only require access to the internet, vulnerable recruits, and global markets of potential victims. This low barrier to entry allows the industry to regenerate rapidly.

Plus, demand from victims worldwide remains high. As long as people respond to romantic overtures, get-rich-quick investment schemes, or social-engineering pitches, the supply side will find recruits to carry out the fraud. Given global inequality, economic instability, and widespread financial insecurity, many victims remain vulnerable.

The Stakes

Economic, Social, and Moral

The rise of scam states threatens more than bank accounts. It undermines governance, fuels human trafficking, erodes the rule of law, and destabilizes economies. Illicit funds from fraud operations can undercut legitimate businesses, distort markets, and corrupt political systems. Entire communities may become dependent on illegal activity for their livelihoods.

For individuals, the consequences are devastating. Scam victims, both those defrauded and those trafficked, suffer financial ruin, mental trauma, and loss of dignity. The toll on families, communities, and trust in institutions is immense.

If the world fails to respond, the “industry” of deception may continue to grow, entrenching itself deeper into national and regional structures.

Conclusion

The emergence of scam states in Southeast Asia marks one of the darkest transformations in the global cyber-fraud landscape. What began as small fraud rings has metastasized into a multi-billion-dollar, deeply embedded criminal economy that traffics human beings, corrupts institutions, and preys on the vulnerable worldwide.

Efforts to dismantle the networks, raids, arrests, sanctions, and international coordination have had some impact. Yet the structural and economic drivers behind the scam factories remain largely unaddressed. Without comprehensive reforms in governance, anti-trafficking enforcement, financial regulation, and regional cooperation, the cycle of exploitation will continue.

For global governments, financial institutions, law enforcement, and civil society, the urgency is clear: this is not a crime wave but a humanitarian and security crisis. Combating it will require a sustained, coordinated, and resource-intensive response, one that treats scam-state dynamics as seriously as drug trafficking, arms smuggling, or human trafficking.

Glossary

- Armed group protection – Armed group protection refers to situations where militias or other armed factions shield scam compounds from law enforcement or local authorities. These groups may receive money, weapons, or political benefits in return. Their involvement makes it harder to shut down scam sites and rescue trafficked workers.

- Barbed-wire compound – A barbed-wire compound is a walled area surrounded by fences and barbed wire where people are held under tight control. In scam states, these compounds are used to confine trafficked workers and prevent escape. The physical barriers reinforce fear and make outside help harder to reach.

- Border town hub – A border town hub is a city or district located near an international border that becomes a center for criminal activity. Scam networks use these locations to move people and money across countries with less oversight. This positioning allows traffickers to recruit in one country and exploit workers in another.

- Civil war instability – Civil war instability describes the breakdown of order when a country’s government and armed groups fight for control. This chaos creates safe spaces for criminal networks to grow. Scam compounds often appear in such regions because authorities are distracted or unable to enforce the law.

- Corruption – Corruption occurs when officials accept bribes, favors, or other benefits in exchange for ignoring or protecting illegal activities. In scam states, corruption allows fraud centers and trafficking operations to keep functioning in plain sight. It blocks justice for victims and undermines trust in government.

- Cyber-enabled financial crime – Cyber-enabled financial crime refers to theft, fraud, and money-moving schemes carried out through the internet and digital systems. Scam centers in Southeast Asia specialize in this type of crime, using online platforms, banking apps, and cryptocurrency to target victims worldwide. The digital nature of these crimes makes them harder to trace and shut down.

- Debt bondage – Debt bondage is a form of modern slavery in which a person is forced to work to “repay” a debt that is often fake, inflated, or impossible to clear. In scam centers, trafficked workers are told they owe money for travel, housing, or “fees” and must keep scamming to pay it back. The debt is used as a tool of control, not as a real financial agreement.

- Economic dependency – Economic dependency happens when a community or region relies heavily on one source of money, even if it is illegal. Scam estates in some areas provide jobs, housing projects, and cash to local economies. This dependence makes residents and leaders less willing to confront the abuse behind the money.

- Forced criminality – Forced criminality means being coerced or threatened into committing crimes against others. Trafficked workers in scam compounds are ordered to defraud victims and may be punished if they refuse. Although they appear to be offenders, they are also victims of exploitation and coercion.

- Forced labor – Forced labor is work that someone is compelled to do under threat, violence, or serious harm, with no real freedom to leave. Scam centers in scam states often rely on forced labor to run their operations. Workers are controlled, abused, and treated as tools to produce illegal profits.

- Foreign transaction tax scam – A foreign transaction tax scam is a fake story used to pressure victims into sending more money by claiming that taxes or transfer fees are required. Scam operators present it as an official charge from banks or governments. Victims are told that unless this “tax” is paid, earlier funds will be frozen or lost.

- Fraud factory – A fraud factory is a large-scale scam center designed to run online crimes like a production line. Workers are assigned scripts, targets, and quotas, and are monitored by managers. The entire setup treats fraud as an industrial business rather than a one-off crime.

- Golden Triangle – The Golden Triangle is a border region where Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand meet, long known for drug trafficking and now for cyber scams. Scam compounds in this area take advantage of weak control and rugged terrain. The location makes access difficult for rescue operations and independent investigation.

- Human trafficking for online scams – Human trafficking for online scams is the recruitment, transport, and control of people who are then forced to carry out internet-based fraud. Victims are lured with fake jobs and end up trapped in scam compounds. Their exploitation is both a trafficking crime and a cybercrime.

- Impunity – Impunity means committing serious offenses without facing punishment or legal consequences. In scam states, powerful networks and their allies often enjoy impunity, even when abuses are documented. This lack of accountability encourages the continued growth of scam operations.

- Industrial-scale online fraud – Industrial-scale online fraud describes scam activity that is carried out in very large volumes, with systems and staffing similar to major corporations. Scam states host centers that target thousands of victims at once, across many countries. The size and organization of these operations multiply the harm done to individuals.

- International sanctions – International sanctions are measures such as asset freezes and travel bans imposed by foreign governments to punish or pressure individuals, groups, or companies. Scam bosses and their networks may be sanctioned for fraud, money laundering, and trafficking. Sanctions aim to cut off profit streams and reduce their global reach.

- Internet blackout – An internet blackout is a deliberate shutdown or restriction of internet services in a specific area. Authorities sometimes use blackouts during raids on scam compounds to disrupt communication and evidence destruction. Blackouts can also harm innocent residents and limit reporting from the area.

- KK Park – KK Park refers to a large compound in Myanmar’s border region that became widely known for cyber scams and forced labor. Reports from survivors describe severe abuse, trafficking, and organized online fraud from this site. Its notoriety symbolizes the scale and brutality of scam estates in conflict zones.

- Mekong subregion – The Mekong subregion covers countries around the Mekong River, including parts of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, and China. Several scam centers and fraud factories are concentrated in this area. Geography, trade routes, and governance gaps all contribute to its role in regional cybercrime.

- Money laundering – Money laundering is the process of hiding the criminal origin of money by moving it through banks, businesses, or cryptocurrencies until it appears legal. Scam networks use complex laundering chains to process stolen funds. This practice makes it harder for victims and authorities to trace or recover losses.

- Narco-state analogy – The narco-state analogy compares scam states to countries where drug cartels dominate politics and the economy. In both cases, illegal industries become central sources of wealth and power. The comparison highlights how deeply cyber scams can penetrate state structures and public life.

- Open-plan scam office – An open-plan scam office is a large room filled with rows of desks, computers, and phones where workers perform fraud tasks under supervision. Supervisors monitor performance, set quotas, and deliver punishments or rewards. The layout supports constant oversight and social pressure to keep scamming.

- Organized crime syndicate – An organized crime syndicate is a structured group that coordinates illegal activities across regions or countries. In scam states, syndicates control recruitment, transport, housing, and laundering linked to scam centers. Their hierarchy and resources allow cyber scams to operate on a global scale.

- Pig-butchering scam – A pig-butchering scam is a long-term fraud where scammers “fatten up” victims with affection and fake profits before “slaughtering” them with large financial demands. Romance, fake investments, and staged trading platforms are used to build trust. Victims often lose life savings because they believe they are investing in a future with someone who cares about them.

- Porous border – A porous border is a frontier where people and goods can cross easily due to weak enforcement or difficult terrain. Traffickers exploit porous borders to move victims into scam compounds with less risk of detection. These weak points make regional cooperation vital in combating scam states.

- Prince Group – The Prince Group is a criminal network identified by foreign governments for its role in scams, trafficking, and money laundering in Southeast Asia. Sanctions against this group targeted its leaders and assets, including real estate investments. The case illustrates how scam profits flow into seemingly legitimate businesses.

- Redemption fee – A redemption fee is a payment demanded from families or victims to “buy back” a trafficked worker’s freedom from a scam compound. This fee can be very high and is often increased without warning. The practice deepens the victim’s exploitation and burdens their family with impossible choices.

- Scam center – A scam center is a physical site where coordinated online fraud operations are carried out. Staff, often trafficked or coerced, work in shifts to contact and manipulate victims around the world. The center provides infrastructure, training, and scripts to maximize criminal income.

- Scam estate – A scam estate is a larger campus or cluster of buildings that hosts multiple scam operations, housing, and support services. These estates may include dormitories, offices, casinos, and shops controlled by the same criminal network. They function as self-contained towns built on exploitation and fraud.

- Scam state – A scam state is a country or region where online fraud and trafficking have grown so powerful that they influence the economy, security forces, and political decisions. Scam activity becomes a major source of income and leverage. This environment makes it extremely hard to protect victims or impose the rule of law.

- Scripted fraud – Scripted fraud is a style of scamming in which workers follow prepared scripts, step-by-step messages, and response trees. These scripts tell them exactly what to say when a victim is hesitant, hopeful, or afraid. The method turns emotional manipulation into a repeatable, trainable process.

- Shell company – A shell company is a business that exists mostly on paper and has little or no real operations. Scam networks use shell companies to hide ownership of compounds, move money, and sign fake contracts. These companies help disguise the true purpose of scam estates.

- Special economic zone – A special economic zone is an area where governments offer tax breaks and relaxed rules to attract investment. Some scam centers have been built inside such zones, using the reduced oversight to hide illegal activities. The promise of jobs and cash often delays stricter enforcement.

- Strike force – A strike force is a specialized law-enforcement team created to target a particular type of crime. The Scam Center Strike Force, formed by the United States (see below), focuses on dismantling Southeast Asian scam networks by following money flows and cooperating with other countries. Such teams signal that cyber scams are being treated as serious international threats.

- Trafficked worker – A trafficked worker is a person who has been recruited, transported, or held through fraud, coercion, or force to perform work against their will. In scam states, many workers are trafficked into online fraud roles rather than traditional labor. Their victim status can be overlooked when authorities focus only on the crimes they were forced to commit.

- Underground banking system – An underground banking system is an informal network used to move money across borders without official records. Scam networks rely on such systems alongside cryptocurrency to transfer victim funds quickly and secretly. This method avoids bank controls and makes investigations harder.

- Victim rescue operation – A victim rescue operation is a coordinated effort by police, embassies, or NGOs to remove people from scam compounds and trafficking sites. These operations may free large numbers of workers, but do not always lead to the arrest of organizers. Proper follow-up is needed so rescued individuals receive protection instead of punishment.

- Whack-a-mole enforcement – Whack-a-mole enforcement describes a pattern where authorities shut down one scam site only for another to appear elsewhere. Criminals adapt by relocating, renaming companies, or shifting to new jurisdictions. This pattern shows why isolated raids are not enough without deeper reforms and sustained pressure.

Reference

- https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/pr/new-scam-center-strike-force-battles-southeast-asian-crypto-investment-fraud-targeting

- https://fortune.com/2025/11/15/southeast-asia-scam-centers-cambodia-myanmar-human-trafficking-cybercrime/

- https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/how-myanmar-became-global-center-cyber-scams

- https://bangkok.ohchr.org/news/2022/online-scam-operations-and-trafficking-forced-criminality-southeast-asia?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- https://www.voanews.com/a/report-southeast-asia-scam-centers-swindle-billions/7655765.html

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2025/dec/02/scam-state-multi-billion-dollar-industry-south-east-asia

- https://www.csis.org/analysis/cyber-scamming-goes-global-unveiling-southeast-asias-high-tech-fraud-factories

- https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/what-are-southeast-asias-scam-centres-why-are-they-being-dismantled-2025-03-04/

- https://www.rusi.org/networks/shoc/informer/trafficking-forced-criminality-rise-scam-centres-southeast-asia

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/10/15/us-uk-sanction-huge-southeast-asian-crypto-scam-network

Author Biographies

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

Table of Contents

- How the “Scam States” of Southeast Asia Developed and are Now Dominating the Region

- How the “Scam States” of Southeast Asia Developed and are Now Dominating the Region

- From Small Frauds to Industrial-Scale Cybercrime

- Root Causes

- Modus Operandi

- Economic and Political Entrenchment

- Human Cost

- From Casinos to Cyber Fraud Factories

- A Multi-Billion-Dollar Shadow Industry

- Trafficking Humans into “Fraud Factories”

- Inside the Compounds

- State Complicity

- China and Regional Governments Push Back

- The International Response

- Looking Forward

- The Stakes

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Reference

LEAVE A COMMENT?

Recent Comments

On Other Articles

- velma faile on Finally Tax Relief for American Scam Victims is on the Horizon – 2026: “I just did my taxes for 2025 my tax account said so far for romances scam we cd not take…” Feb 25, 19:50

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “Yes, this is a scam. For your own sanity, just block them completely.” Feb 25, 15:37

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “She goes by the name of Sanrda John now” Feb 25, 10:26

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “So far I have not been scam out of any money because I was aware not to give the money…” Feb 25, 07:46

- on Love Bombing And How Romance Scam Victims Are Forced To Feel: “I was love bombed to the point that I would do just about anything for the scammer(s). I was told…” Feb 11, 14:24

- on Dani Daniels (Kira Lee Orsag): Another Scammer’s Favorite: “You provide a valuable service! I wish more people knew about it!” Feb 10, 15:05

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “We highly recommend that you simply turn away form the scam and scammers, and focus on the development of a…” Feb 4, 19:47

- on The Art Of Deception: The Fundamental Principals Of Successful Deceptions – 2024: “I experienced many of the deceptive tactics that romance scammers use. I was told various stories of hardship and why…” Feb 4, 15:27

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “Yes, I’m in that exact situation also. “Danielle” has seriously scammed me for 3 years now. “She” (he) doesn’t know…” Feb 4, 14:58

- on An Essay on Justice and Money Recovery – 2026: “you are so right I accidentally clicked on online justice I signed an agreement for 12k upfront but cd only…” Feb 3, 08:16

ARTICLE META

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims

- Enroll in FREE SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery

If you are looking for local trauma counselors please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org or join SCARS for our counseling/therapy benefit: membership.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

A Note About Labeling!

We often use the term ‘scam victim’ in our articles, but this is a convenience to help those searching for information in search engines like Google. It is just a convenience and has no deeper meaning. If you have come through such an experience, YOU are a Survivor! It was not your fault. You are not alone! Axios!

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish, Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors experience. You can do Google searches but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

Statement About Victim Blaming

SCARS Institute articles examine different aspects of the scam victim experience, as well as those who may have been secondary victims. This work focuses on understanding victimization through the science of victimology, including common psychological and behavioral responses. The purpose is to help victims and survivors understand why these crimes occurred, reduce shame and self-blame, strengthen recovery programs and victim opportunities, and lower the risk of future victimization.

At times, these discussions may sound uncomfortable, overwhelming, or may be mistaken for blame. They are not. Scam victims are never blamed. Our goal is to explain the mechanisms of deception and the human responses that scammers exploit, and the processes that occur after the scam ends, so victims can better understand what happened to them and why it felt convincing at the time, and what the path looks like going forward.

Articles that address the psychology, neurology, physiology, and other characteristics of scams and the victim experience recognize that all people share cognitive and emotional traits that can be manipulated under the right conditions. These characteristics are not flaws. They are normal human functions that criminals deliberately exploit. Victims typically have little awareness of these mechanisms while a scam is unfolding and a very limited ability to control them. Awareness often comes only after the harm has occurred.

By explaining these processes, these articles help victims make sense of their experiences, understand common post-scam reactions, and identify ways to protect themselves moving forward. This knowledge supports recovery by replacing confusion and self-blame with clarity, context, and self-compassion.

Additional educational material on these topics is available at ScamPsychology.org – ScamsNOW.com and other SCARS Institute websites.

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this article is intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here to go to our ScamsNOW.com website.

Thank you for your comment. You may receive an email to follow up. We never share your data with marketers.