SCARS Institute’s Encyclopedia of Scams™ Published Continuously for 25 Years

Understanding Scam Victims

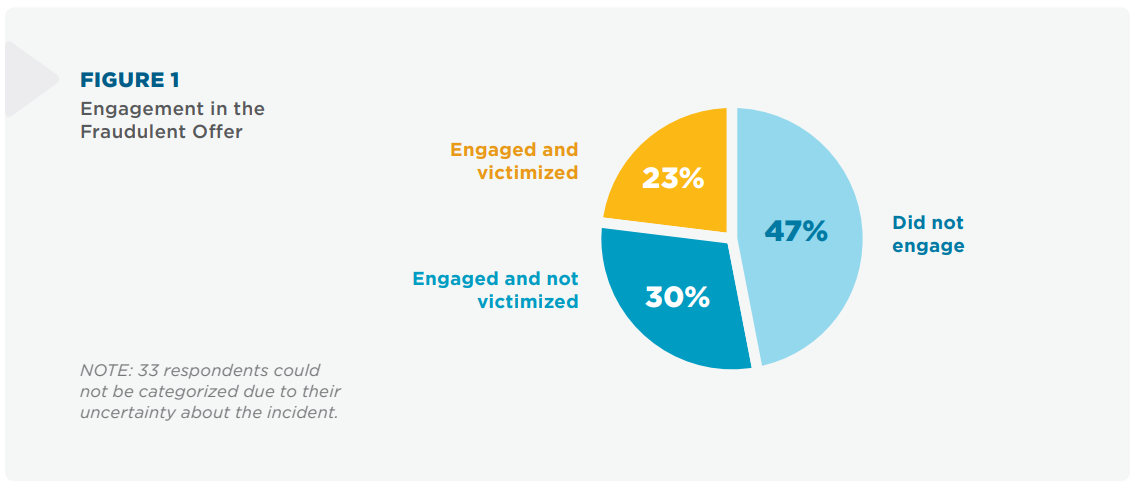

Victimization by scams and fraud depends, in part, on two-way engagement between the target of the scam and the fraudster. Some individuals simply do not engage with a scammer; others engage but at some point recognize the deception and cease engagement. Still others engage with the fraud and lose money (sometimes a lot of money). Despite the enormous personal and financial costs of fraud victimization, little is understood about the factors that differentiate these three groups.

In this survey of 1,408 Americans and Canadians who were targeted and reported a scam, nearly half (47 percent) did not engage with the fraudster and so were not victimized. Thirty percent engaged but did not lose money, yet 23 percent engaged and ultimately lost money. The type of scam and the method by which the

respondents were exposed to the offer were highly associated with engaging and losing money. Specifically, scams involving online purchases correlated with the highest levels of engagement and victimization. With regard to modality, survey respondents who engaged and became victims were more likely to report being exposed to those scams on a website or through social media than via telephone, mail, or email. Social isolation and low levels of financial literacy were also associated with engaging and losing money. This research also found that prior knowledge of scams and fraud can reduce susceptibility.

Please note that this study did not really examine the most common relationship scam: romance scams. However, this information does provide significant insights into victimology that can be applied to all scam victims.

AUTHORS

- Marti DeLiema, Ph.D., Stanford Center on Longevity

- Emma Fletcher, Federal Trade Commission

- Christine N. Kieffer, FINRA Foundation

- Gary R. Mottola, Ph.D., FINRA Foundation

- Rubens Pessanha, Ed.D., MBA, PMP, GPHR, SPHR, SHRM-SCP, International Association of Better Business Bureaus, Inc.

- Melissa “Mel” Trumpower, BBB Institute for Marketplace Trust

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Craig Honick of Metro Tribal for his work on survey design and data collection, and Susan Arthur for her comments on earlier drafts of the paper. We would also like to thank the Better Business Bureau for access to data from their BBB Scam Tracker database and the FINRA Foundation for funding the research

Background

Approximately one in ten U.S. adults are victims of fraud each year (Anderson, 2013), and self-reported fraud loss complaints to the Federal Trade commission’s (FTC) Consumer Sentinel Network increased by about 34 percent from 2017 to 2018

(authors’ calculations using FTC consumer complaint data). NOTE: SCARS is an FTC Sentinel Reporting partner.

The FTC received more than 372,000 fraud complaints with more than $1.5 billion in direct losses in 2018, and another 1.1 million fraud complaints with no reported losses (FTC, 2019). In 2017 and 2018, the FINRA Investor Education Foundation, in concert with BBB Institute for Marketplace Trust and the Stanford Center on Longevity, sponsored a study to uncover the process of fraud victimization and understand the factors associated with losing money. The study involved a comparison of those exposed to a scam who lost money (victims) to those exposed to a scam who successfully avoided losing money (targets). The goal of the research was to better understand the conditions under which scam targets do not become victims in order to develop more focused and effective public education based on those protective factors.

All participants in this two-phase study reported a fraud to BBB Scam Tracker, an online fraud reporting tool of the Better Business Bureau. The first phase of the research comprised one-hour interviews with 18 consumers, some of whom reported being a scam victim (monetary loss) and others who reported being targets but not victims (no monetary loss). In the second phase of the study, the research team administered a 15-minute online survey to 1,408 consumers who filed a fraud tip or report through BBB Scam Tracker (see Methodology section for more details). The survey questions were informed by the qualitative findings from the first phase of the research, and the survey results are the focus of this issue brief. The survey sample skewed older, female, and college-educated.

Sample sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Appendix A (see the PDF below)

Level of Engagement

The first step to being victimized by a scam is to engage with a fraudster, so it is heartening to see that nearly half (47 percent) of survey respondents rejected the offer outright (Figure 1). They hung up the phone, closed the link, ignored the email, threw away the mailer, deleted the friend request, or otherwise refused to comply. This refusal to engage was the predominant response in bogus tax and other debt collection scams, and in phishing scams where fraudsters impersonate

a trustworthy entity to mislead the target into giving them money. However, 30 percent of respondents engaged to some degree, but ultimately did not lose money, while 23 percent engaged with the fraudster or offer and lost money.

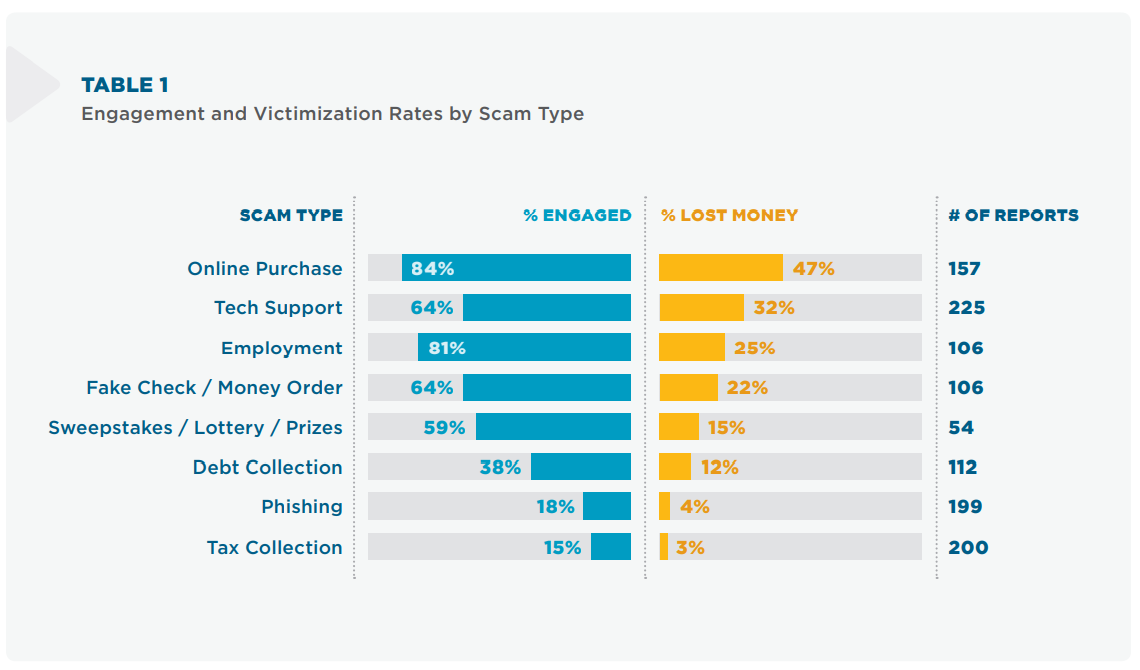

Type of Scam

Please note that this study did not really examine the most common relationship scam: romance scams.

Victimization rates in this sample varied dramatically by scam type. Among the fraud categories with more than 50 respondents, the highest victimization rates were (Table 1) online purchase scams, tech support scams, employment scams, and fake check/money order scams. The victimization rates were very low for phishing and tax collection scams. Median losses in this survey were $600, while median losses in the 2018 BBB Scam Tracker Risk Report were only $152. Those who filed BBB Scam Tracker reports with higher loss amounts may have been more motivated to respond to the survey to share their experience.

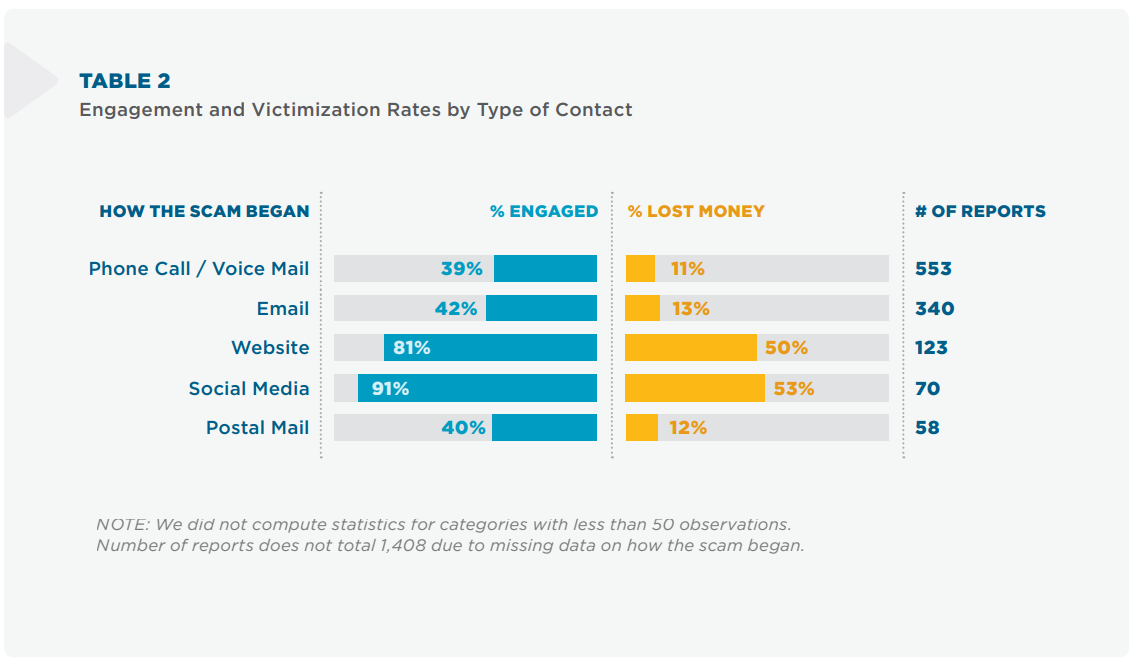

Method of Contact

Whether or not a person engaged with the scam and lost money was highly associated with the method in which they were exposed to the offer (Table 2). Phone and email were the most common methods of contact, but relatively few respondents reported losing money as a result of these scams. For example, 39 percent of respondents who said they were contacted by phone engaged with a scammer and only 11 percent lost money. In contrast, of those contacted by email, 42 percent engaged with the scammer and only 13 percent lost money. Of those who said they were exposed to a scam on social media, 91 percent engaged and 53 percent lost money. Similarly, 81 percent of respondents who were exposed to a fraud via a website said they engaged and 50 percent lost money.

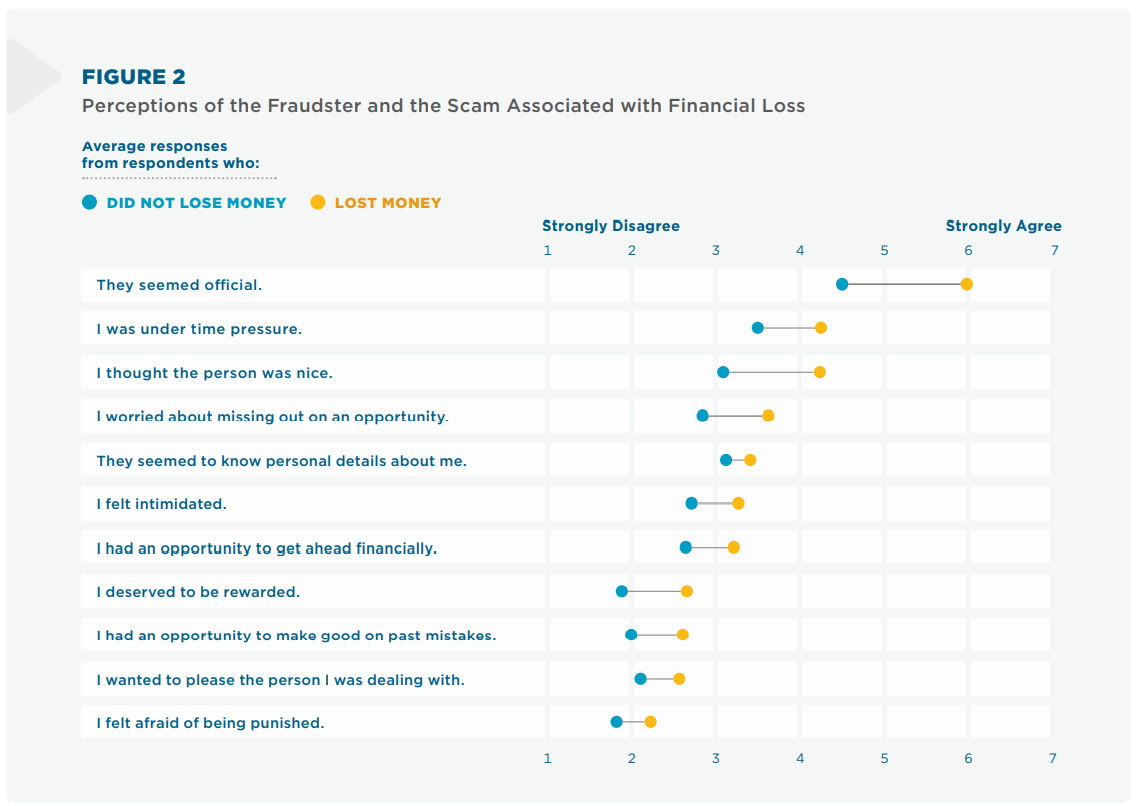

Self-Reported Reasons for Engaging

Using a seven-point Likert scale, where “1” was “strongly disagree” and “7” was “strongly agree”, we asked those who engaged with the scam a series of questions to understand the factors leading to monetary loss. As shown in Figure 2, on a range of factors that the qualitative portion of this study suggested were related to fraud victimization, respondents who engaged and lost money scored higher than respondents who engaged and did not lose money. For example, the more a respondent felt that the person/organization seemed official, the more likely they were to lose money. Respondents were also more likely to lose money

the more they felt under time pressure, believed the opportunity would help them get ahead financially, felt that it was “their time” and that they deserved to be rewarded, wanted to make good on past mistakes, and/or were intimidated by the person they were dealing with. Those who lost money were also more likely to agree that they wanted to impress the person they were dealing with and worried about missing out on an opportunity. All of these differences were statistically significant at p<.01. These findings align with common persuasion techniques that fraudsters use to convince targets to comply (Cialdini, 2001).

Victims Reported:

- “Sounded like a sheriff’s deputy and he was threatening me with immediate arrest if I didn’t comply.”

- “I was caught off guard and insufficiently informed.”

Demographics

We found small to no difference in engagement behavior or victimization rates by gender, ethnicity, education, or employment status, though we did find an age-based effect. On average, those who lost money were 2-3 years younger than those who were targeted for a scam but did not engage.4 This is consistent with published data on fraud reports to both the FTC’s Consumer Sentinel Network and BBB Scam Tracker — older adults report more scams in which they were targeted but not victimized compared to younger adults who are more likely to report scams that resulted in a financial loss (BBB Institute, 2019; FTC, 2019).

Further, those who engaged and lost money were less likely to be married and more likely to be widowed or divorced.

Respondents were more likely to be victimized if they did not have anyone to discuss the offer with. It is noteworthy that single, divorced, and widowed respondents were more likely to indicate that they did not have anyone to discuss things with compared to married respondents and those living with a partner. Those who engaged, in general, and those who lost money expressed significantly higher feelings of loneliness. Specifically, losing money was associated with more frequent feelings of being left out, lacking companionship, and being isolated from others (meanvictim=4.5, mean non-victim=4.0, p<.001).

Respondents were more likely to be victimized if they did not have anyone to discuss the offer with.

Financial Insecurity

Prior work by Anderson (2013) and AARP (2003) has indicated that individuals who are under financial strain might be more susceptible to scams, especially scams that promise financial rewards or an opportunity to get out of debt. In the present study, low household income ($50,000 and below) was significantly associated with engaging and losing money in a scam (p<.001). In addition, those who lost money were significantly more likely than non-victims to show signs of financial insecurity. This included reporting that they spend more than their monthly income (23 percent versus 17 percent; p=.017), and that they “probably could not” or “certainly could not” come up with $2,000 if an unexpected need arose within the next month (38 percent versus 20 percent; p<.001).

Victims were also significantly more likely to agree with the statement “I have too much debt right now” (meanvictim=3.6 mean non-victim=3.1 out of seven, p=.001). Levels of financial insecurity varied by scam type. For example, respondents who reported advance fee loan, investment, and sweepstakes/lottery/prizes scams were more likely than other reporters to show signs of financial insecurity. It is also possible that the scams themselves contributed to the financial insecurity of the victims.

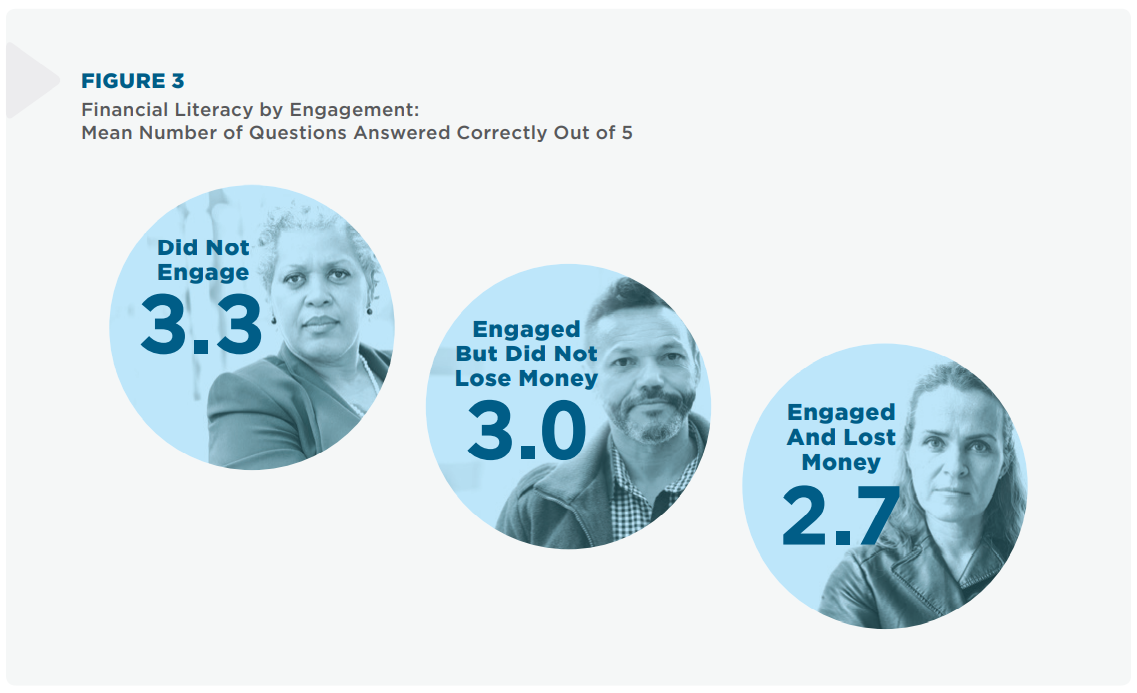

Financial Literacy

Participants were asked five questions to gauge their financial knowledge. As seen in Figure 3, those who ended the scam attempt immediately scored significantly higher on this five-item quiz, an average of 3.3 correct answers out of a total of five.6 The average score of those who engaged with the scam was 3.0, and of those who lost money was 2.7 (p<.001).

Those who ended the scam attempt immediately scored significantly higher.

Intervention By Organizations — The Role Of Structural Protections

Among those who engaged with the scam, 20 percent reported that an organization, company, or agency intervened or tried to intervene to stop the scam. People described interventions by bank tellers and employees of wire transfer services and other financial services companies. Some organizations train their frontline employees to recognize the indicators of fraud (e.g., large cash bank withdrawals or purchases of high-dollar value gift cards). The survey results show that 51 percent of people who reported a third-party intervention were able to avoid losing money. This is a promising finding given that these interventions

generally occur at a point when consumers are on the cusp of sending money to a scammer (e.g., at a store checkout counter buying gift cards). The work of cashiers, bank tellers, and other vigilant employees can serve as an important last line of defense for consumers who might otherwise become fraud victims.

We know from previous studies that individuals engaging with scammers are likely to be in a heightened emotional state that impairs their ability to respond

appropriately to misleading information (Kircanski et al., 2018). Further, in many cases, fraudsters have developed scripts designed to negate intervention by third parties, such as telling their targets not to speak to anyone and even coaching them on how to respond to a cashier’s or bank teller’s questions and protests. Additional research in this area could help businesses and others who are well-positioned to intervene to develop more effective training programs and intervention techniques.

“I took the check to the bank, they notified me [it] was fraud.”

“I called my credit card [provider] on another phone, gave her the billing name and she said, ‘Hang up.’ ”

PERCEPTION OF VICTIMS

” Looking back, it was so obvious that it was a scam. I guess I wanted it to be true. I didn’t read the comments until it was too late. I’m so embarrassed.”

SCARS NOTE: this is a reflection of “Hindsight Bias” but that perception is not real.

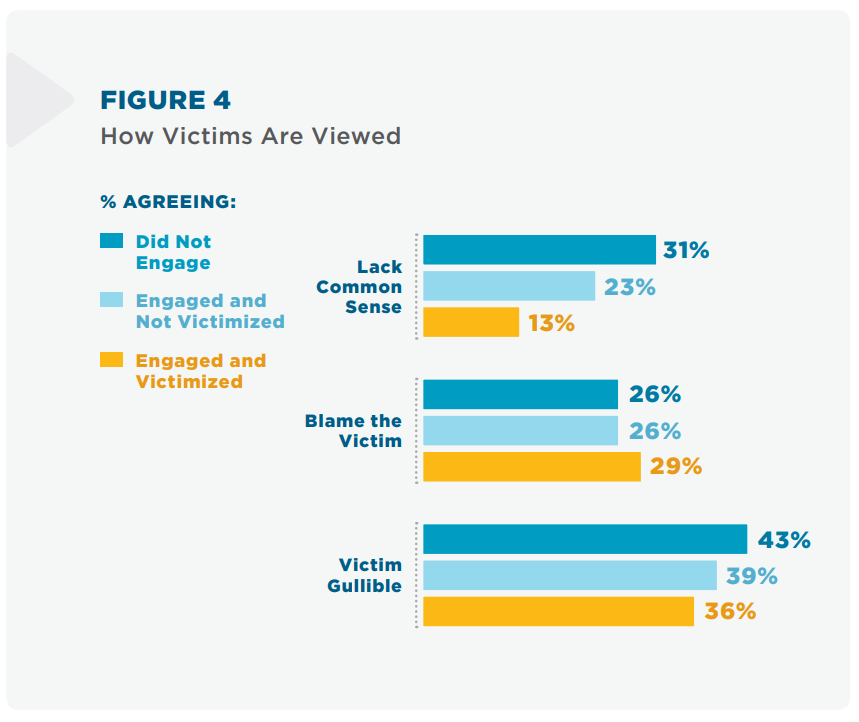

The survey also sought to gauge how respondents view scam victims, in general. A large percentage of respondents believe that victims of fraud are gullible — from a high of 43 percent for those who did not engage to a low of 36 percent for those who lost money (Figure 4). It is noteworthy that nearly a third of those who lost money believe it is likely the victims’ fault for being defrauded. When asked if scam victims lack common sense, only 13 percent of victims believe that to be true, compared to a third of those who did not engage.

Reporting rates for fraud and scams are low, and it is possible that widely held negative views associated with victims contributes to a person’s reluctance to admit that they were scammed. This could also deter victims from seeking assistance in dealing with the consequences of fraud, whether financial, psychological, or emotional assistance. Earlier work by the FINRA Foundation (2015) found that the non-financial costs of fraud (e.g., stress, health problems) are widespread among victims, and nearly two-thirds (65 percent) report experiencing at least one type of non-financial cost to a serious degree. The FINRA Foundation study also found that 47 percent of victims blamed themselves. These findings suggest that professional victim support groups could play an important role in destigmatizing the experience and helping those who have lost money recover from fraud.

SCARS NOTE: SCARS provides professional trauma-informed support groups for men and women scam victims. Look for our groups on Facebook.

PREVENTING FINANCIAL FRAUD

Knowledge is Power

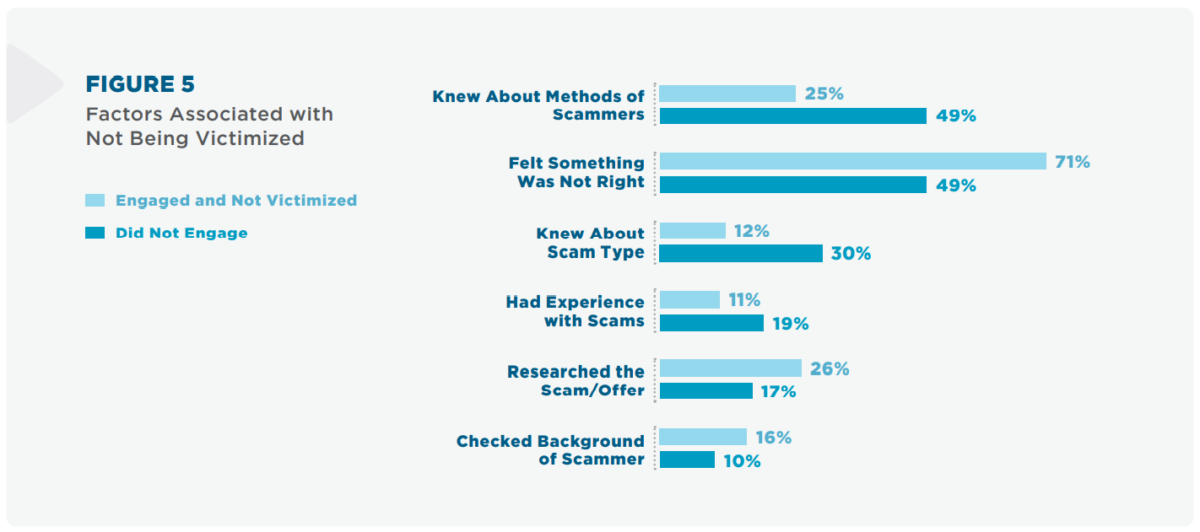

Knowing about specific types of scams and understanding the general tactics that scammers use can help a scam target avoid becoming a victim. In this survey, 30 percent of respondents who did not engage knew about the scam before they were targeted compared to 12 percent of people who engaged but were not victimized (Figure 5). Respondents who had heard about the scam before were significantly less likely to lose money (9 percent versus 34 percent, p<.001). Among respondents who did not engage with the scammer, almost half (49 percent) reported knowing about the methods and behaviors of scammers in general

compared to only 25 percent of those who did engage but were not victimized. Those who did not engage were also more likely to say they had experience with scams than those who engaged but were not victimized, 19 percent versus 11 percent, respectively. This indicates that having prior knowledge about fraud, even generally, is particularly helpful in avoiding victimization.

The majority of fraud targets did not report looking into the scam or the scammer while they were being targeted. For instance, among those who did not engage, 17 percent researched the offer and 10 percent checked the background of the scammer. For those who engaged but were not victimized, 26 percent researched the offer, and 16 percent checked the background of the scammer. Last, among those who engaged but were not victimized, by far the most common reason cited for not being victimized was that they felt something was not right about the situation.

Among respondents who engaged, those who chose not to discuss the solicitation with anyone while it was happening were significantly more likely to lose money, as were those who did not have anyone available to discuss it with.

” I talked to my kids and they said they were pretty sure it was a scam.”

In the Targets’ Own Words

Respondents who were suspicious about the offer but who continued to engage were asked what would have helped them avoid engaging altogether.

One individual stated, “…if I had done the research before making the purchase.” Other suggestions were to speak with someone prior to engaging, use other websites to verify the pricing of the product, check the BBB website for complaints about the organization, and search for the address of the organization on Google Maps. One person said, “not being distracted.” Recommendations also included looking for clues that the offer is fake, such as misspelled words in the

message or a spoofed email address.

Where do victims and non-victims learn about fraud?

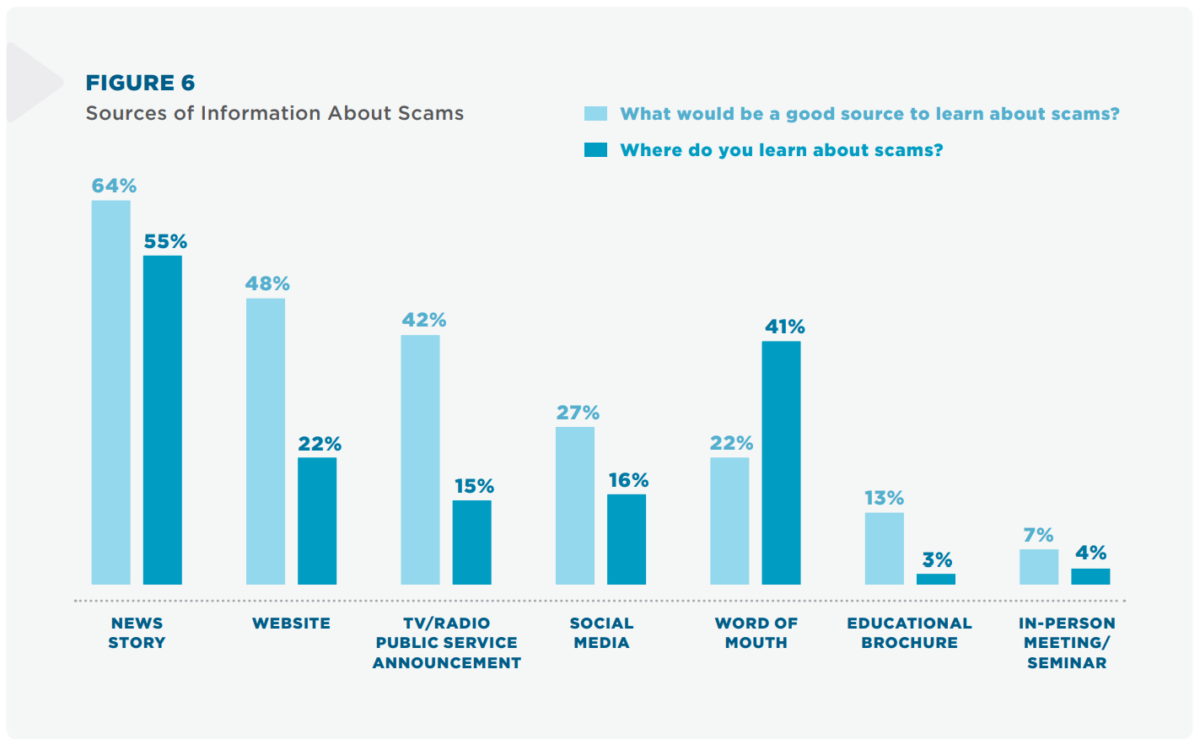

We asked respondents what they believed would be a good source of information on fraud and scams, and where they have actually received such information. While nearly half (48 percent) believed websites (such as RomanceScamsNOW.com) would be a good source of information, few actually reported

obtaining information about fraud and scams from websites (Figure 6).

It is noteworthy that 42 percent of respondents believed that a public service announcement (PSA) on TV or radio would be helpful, but few respondents (15 percent) noted this as an actual source of information where they previously learned about fraud, likely because PSAs about scams are not very common. News stories were, by far, the most popular answer. Conversely, while respondents did not believe word of mouth is a particularly good source of information about scams, more than 40 percent of respondents said they had obtained information about frauds in this way. Educational brochures and in-person meetings/

seminars were infrequently mentioned as good or actual sources of information about scams and fraud. However, they may have an indirect effect on reducing fraud by fueling the communication of information on frauds by word of mouth. While it is beyond the scope of this study to determine the actual effectiveness of sources of information, these findings suggest that the news media has an important role to play in making consumers aware of scams.

IMPLICATIONS

In terms of protective factors, knowledge is power.

The path to victimization begins with engagement, and there are a number of factors that increase the likelihood of both engaging with a fraudulent offer and losing money.

- The manner in which consumers are contacted plays a significant role in whether or not they engage and become victims. Because those contacted via digital means (social media and website) appear from this study to have high engagement and victimization rates, consumers should be particularly careful when sending money based on a digital message or ad.

- The perception that a fraudster is “official” is highly associated with victimization. As titles and designations are easily faked, consumers should independently verify the identity of anyone who claims to be an authority and asks for money or information (e.g., call the agency directly to confirm, or use an online tool such as FINRA BrokerCheck).

- Financial insecurity appears to increase the likelihood of victimization, as do low levels of financial literacy.

- More than half of people who reported a third-party intervention were able to avoid losing money. This is a promising finding and speaks to the potential of this approach to reduce fraud victimization given these interventions generally occur at a point when consumers are on the cusp of sending money to a scammer.

- In terms of protective factors, knowledge is power. Prior knowledge about fraud, even generally, is particularly helpful in avoiding victimization.

Before complying with a solicitation, consumers should consult with those around them to verify the legitimacy of the offer or the threat. This strategy is helpful because it harnesses collective knowledge about scams and persuasion tactics from friends, family, neighbors, and whoever else is present at the time of the solicitation. These people might encourage the target to pause and take time to assess the situation.

Incorporating these protective behaviors into routine interactions with sellers and other agents of influence could help consumers avoid fraud, but knowing about common scams and the tactics of persuasion ahead of time is potentially even more effective at preventing fraud than doing research in the moment. “Trusting your gut” when you sense something might be wrong with a situation can also serve as a protective factor.

However, if your instincts are leading you in the opposite direction and telling you to engage, “trusting your gut” could lead to victimization.

Therefore, a wise strategy is to pause, talk it over with others, and do some research before sending any money or sharing personally identifiable information. Further, given the generally negative perception of victims, support groups can help individuals who have experienced fraud cope with the social and emotional consequences. And the news media can play a role in spreading awareness of how to spot, avoid, and report scams. The media can also help send an empowering message, and perhaps change the negative stigma associated with victimization, by giving people who have experienced a scam the opportunity to help others by sharing their story.

SCARS Note: SCARS provides confidential and private support groups where victims can feel at ease and to be able to share their stories and recover without our trauma-informed approach. For men go here / For women go here — We separate genders because of the difference in psychologies between men and women, and also to provide greater comfort for the victim members when discussing aspects of their scams.

Knowing about common scams and persuasion tactics ahead of time is potentially even more effective at preventing fraud than doing research in the moment.

For The Remained Of The Study Information View The PDF Below

[pdf-embedder url=”https://romancescamsnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/exposed-to-scams-what-separates-victims-from-non-victims_0_0.pdf” title=”Exposed to Scams: WHAT SEPARATES VICTIMS FROM NON-VICTIMS?”]

-/ 30 /-

What do you think about this?

Please share your thoughts in a comment below!

Table of Contents

LEAVE A COMMENT?

Thank you for your comment. You may receive an email to follow up. We never share your data with marketers.

Recent Comments

On Other Articles

- on Finally Tax Relief for American Scam Victims is on the Horizon – 2026: “I just did my taxes for 2025 my tax account said so far for romances scam we cd not take…” Feb 25, 19:50

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “Yes, this is a scam. For your own sanity, just block them completely.” Feb 25, 15:37

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “She goes by the name of Sanrda John now” Feb 25, 10:26

- on Reporting Scams & Interacting With The Police – A Scam Victim’s Checklist [VIDEO]: “So far I have not been scam out of any money because I was aware not to give the money…” Feb 25, 07:46

- on Love Bombing And How Romance Scam Victims Are Forced To Feel: “I was love bombed to the point that I would do just about anything for the scammer(s). I was told…” Feb 11, 14:24

- on Dani Daniels (Kira Lee Orsag): Another Scammer’s Favorite: “You provide a valuable service! I wish more people knew about it!” Feb 10, 15:05

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “We highly recommend that you simply turn away form the scam and scammers, and focus on the development of a…” Feb 4, 19:47

- on The Art Of Deception: The Fundamental Principals Of Successful Deceptions – 2024: “I experienced many of the deceptive tactics that romance scammers use. I was told various stories of hardship and why…” Feb 4, 15:27

- on Danielle Delaunay/Danielle Genevieve – Stolen Identity/Stolen Photos – Impersonation Victim UPDATED 2024: “Yes, I’m in that exact situation also. “Danielle” has seriously scammed me for 3 years now. “She” (he) doesn’t know…” Feb 4, 14:58

- on An Essay on Justice and Money Recovery – 2026: “you are so right I accidentally clicked on online justice I signed an agreement for 12k upfront but cd only…” Feb 3, 08:16

ARTICLE META

Important Information for New Scam Victims

- Please visit www.ScamVictimsSupport.org – a SCARS Website for New Scam Victims & Sextortion Victims

- Enroll in FREE SCARS Scam Survivor’s School now at www.SCARSeducation.org

- Please visit www.ScamPsychology.org – to more fully understand the psychological concepts involved in scams and scam victim recovery

If you are looking for local trauma counselors please visit counseling.AgainstScams.org or join SCARS for our counseling/therapy benefit: membership.AgainstScams.org

If you need to speak with someone now, you can dial 988 or find phone numbers for crisis hotlines all around the world here: www.opencounseling.com/suicide-hotlines

A Note About Labeling!

We often use the term ‘scam victim’ in our articles, but this is a convenience to help those searching for information in search engines like Google. It is just a convenience and has no deeper meaning. If you have come through such an experience, YOU are a Survivor! It was not your fault. You are not alone! Axios!

A Question of Trust

At the SCARS Institute, we invite you to do your own research on the topics we speak about and publish, Our team investigates the subject being discussed, especially when it comes to understanding the scam victims-survivors experience. You can do Google searches but in many cases, you will have to wade through scientific papers and studies. However, remember that biases and perspectives matter and influence the outcome. Regardless, we encourage you to explore these topics as thoroughly as you can for your own awareness.

Statement About Victim Blaming

SCARS Institute articles examine different aspects of the scam victim experience, as well as those who may have been secondary victims. This work focuses on understanding victimization through the science of victimology, including common psychological and behavioral responses. The purpose is to help victims and survivors understand why these crimes occurred, reduce shame and self-blame, strengthen recovery programs and victim opportunities, and lower the risk of future victimization.

At times, these discussions may sound uncomfortable, overwhelming, or may be mistaken for blame. They are not. Scam victims are never blamed. Our goal is to explain the mechanisms of deception and the human responses that scammers exploit, and the processes that occur after the scam ends, so victims can better understand what happened to them and why it felt convincing at the time, and what the path looks like going forward.

Articles that address the psychology, neurology, physiology, and other characteristics of scams and the victim experience recognize that all people share cognitive and emotional traits that can be manipulated under the right conditions. These characteristics are not flaws. They are normal human functions that criminals deliberately exploit. Victims typically have little awareness of these mechanisms while a scam is unfolding and a very limited ability to control them. Awareness often comes only after the harm has occurred.

By explaining these processes, these articles help victims make sense of their experiences, understand common post-scam reactions, and identify ways to protect themselves moving forward. This knowledge supports recovery by replacing confusion and self-blame with clarity, context, and self-compassion.

Additional educational material on these topics is available at ScamPsychology.org – ScamsNOW.com and other SCARS Institute websites.

Psychology Disclaimer:

All articles about psychology and the human brain on this website are for information & education only

The information provided in this article is intended for educational and self-help purposes only and should not be construed as a substitute for professional therapy or counseling.

While any self-help techniques outlined herein may be beneficial for scam victims seeking to recover from their experience and move towards recovery, it is important to consult with a qualified mental health professional before initiating any course of action. Each individual’s experience and needs are unique, and what works for one person may not be suitable for another.

Additionally, any approach may not be appropriate for individuals with certain pre-existing mental health conditions or trauma histories. It is advisable to seek guidance from a licensed therapist or counselor who can provide personalized support, guidance, and treatment tailored to your specific needs.

If you are experiencing significant distress or emotional difficulties related to a scam or other traumatic event, please consult your doctor or mental health provider for appropriate care and support.

Also read our SCARS Institute Statement about Professional Care for Scam Victims – click here to go to our ScamsNOW.com website.

This article brought up a lot of reactions/thoughts of how as a victim there were factors out of my control and in my control (in hindsight). The insight I gained from this article is in no way to “victim blame”, but puts things in perspective.

The fact that I am a widow and live alone (I believe) increased the loneliness factor and the inability to easily discuss the initial contact with the scammer.

I had known of romance scams through dating sites (unfortunately, I was involved with two – one generated on the dating site Plenty of Fish and the other generated on the dating site Hinge), but was not aware that my engaging with another player in a gaming app would lead to becoming involved in a romance scam.

In hindsight, there were times that I spoke to others about the scam and was warned that it was a scam. If I had listened to a bank representative at a specific time during the scam, I may have not have lost as much money as I did; I was so convinced at that time that the relationship was real that no one could convince me otherwise.

It is hard to keep informed of all the scams that targets can be exposed to – scammers are coming up with new ways to rob people.

The truth is that the types of scams do not matter that much single they follow similar methodologies. Avoiding scams is not about knowledge of every scam, it is about changing behaviors.

The statistics offered in this article are interesting. Since my fraud was primarily a romance scam – solely based on an intense love relationship, I did try to apply some of the information presented to my own situation. In looking back to see if any of the credit cards I used closed transactions at point of sale because it was thought to be fraud – only one did so. But it was the company that was used to withdraw funds from two checking accounts at the time of my identity theft. The company tried to stop the purchase transactions, but during the identity theft allowed two significant withdrawal of funds from separate checking accounts. Their reason: it appeared that I was the person who set up the withdrawals through their mobile banking app – which I never used. When I questioned the dollar amounts withdrawn in comparison to other monthly payments made to them they questioned me that maybe I had added extra zeros and didn’t catch my mistake. The other credit cards involved in my fraud all allowed the transactions to go through without tagging them as fraud. In the case of my fraud, I thought my scammer was the REAL person – the celebrity. There were such small inconsistencies in persona that they didn’t signal red flags. That said, I did try to research the email addresses that were given to me. They were gmail emails. I thought that was odd but in my corporate days I did have customers with gmail emails. In the research there was no conclusive information that the email was not attached to the entity (management or otherwise). Nothing came up in my search that would indicate I should take precaution. So the fraud continued that included a total span of about 3 weeks of either sending money or purchasing gift cards. Interestingly enough the anger displayed by the scammer was more of a deterrent than anything. Anger triggers me, intense anger is frightening to me after being abused. Anger stopped me providing anything additional to the scammer. I would “chat” with them. They would attempt to get me to do something else like get involved with crypto or registering a LLC and opening a business checking account, but I would not comply. I engaged and I lost money.

I almost avoided my pig butcher scam but in the end lost a great deal of money. I had read about PBS, my kids were telling me it was a scam, and the bank managers really tried hard to stop me but I thought my situation was different. It wasn’t.

You should go back and let the bank staff know that YOU know they were right and that appreciate their efforts.